Literature 2.0

In March 2016, 34-year-old online writer Zhang Wei, who goes by the penname Tangjia Sanshao, became the first Chinese author to earn more than 100 million yuan (about US$14.5 million) a year. He topped the Chinese Online Writers Rich List for the fourth consecutive year with royalties of 110 million yuan (around US$16 million). Within less than two decades, China’s online literature has grown from a handful of writers sharing works online to daily publication volume equal to annual publications of a medium-sized publishing house. The volume of online literature readers has grown to over 300 million in China. Experts estimate that the value of the online literature industry this year will reach as high as 9 billion yuan (US$1.3 billion).

Rapid Rise

Generally, online literature refers to works ranging from short stories to full novels that are published and consumed online. Common subject matter includes time travel, science fiction, fantasy, game-based fiction, and mystery fiction. Of the many outstanding writers that have emerged from online literature, Tangjia Sanshao is renowned for his persistent diligence: He has written seven to eight thousand words every day for 10 consecutive years. The fantasy novel Coiling Dragon by Zhu Hongzhi, whose penname is I Eat Tomatoes, accumulated viewership of 80 million within 13 months after it was published online. Zhou Dedong, former editor-in-chief of Youth Digest (one of the most popular digest magazines among young people in China), has been praised as the godfather of China’s cliffhangers for his popular online horror novels.

From the publication of the first online work to its current mammoth state, the development of Chinese online literature can be divided into three phases.

The period from 1998 to 2002 can be called the nascent phase. From March to May of 1998, Tsai Chih-heng’s serial The First Intimate Contact was reposted by many famous websites. This novel introduced the concept of “online literature” to many for the first time. This novel is still considered one of the founding fathers of the trend.

From then on, more and more writers began to publish serials online, and others began to share poetry as well as prose.

Online literature entered a phase of explosive growth from 2002 to 2010. The VIP mode of monetizing work created by Qidian.com, an online literature site, turned out to be a watershed move, and other websites quickly followed suit, making online literature an emerging industry with great potential. Common writers could make a living by writing online. In the period of less than a decade, the online literature industry drew nearly 100,000 writers and almost 50 million readers.

Over the same period, fantasy novels went mainstream. Entertainment elements of Japanese comics and Hollywood movies were combined with local culture in the novels. “At first, there was no obvious difference between online literature and traditional literature,” remarked famous Chinese writer Cai Jun. “Except for The First Intimate Contact, which was about cyber love, most online works were just traditional literature published online. But now many online serials are very long stories about tomb robbery or time travel.”

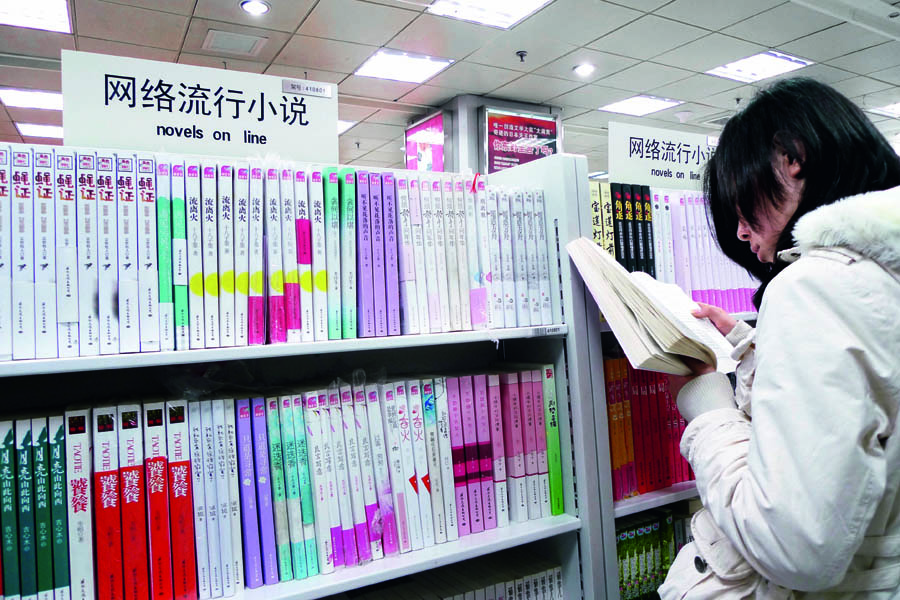

Since 2010, China’s online literature has merged with rise of mobile devices and made paper books near obsolete. Online readership continues growing and the threshold to be a writer has further dropped. Smartphones have facilitated both reading and payment. Writers have more sources of income and channels to contribute. However, breakthroughs on content are yet to come.

Online literature, which was originally read by only a few people, is now widespread and commercial. Three major factors contributed to its rise:

First, it is inclusive. Many who dream of becoming a professional writer or simply enjoy writing as a hobby can easily publish work online without constraints of the traditional publication sector. By the end of December 2015, China’s online literature websites had signed 2.5 million writers.

Second, writers and their readers can interact online instantly. The moment new chapters are released, readers can comment immediately. Fans always encourage the writer, raise questions or express how they hope the plot will unfold, making writing a more interactive process.

Third, consumption of online literature resembles that of fast food in many ways. “When reading online fiction, I don’t need to think about it too hard,” remarked one online reader. “It’s just entertainment.” In this regard, the industry is similar to TV and movies. The majority of online works deserve to be read only once. Few works have been called classics or maintained long-term popularity.

Problems and Prospects

After rampant growth of online literature over the past two decades, some problems have emerged, which beg special attention.

First, excellent work is extremely rare, considering the massive volume. Although hundreds of millions of words are published every day, Wu Wenhui, CEO of China Reading Limited, pointed out that online literature, which is enjoying prosperity, struggles with a shortage of outstanding original works and persistent plagiarism.

Second, over-commercialization harms the spirit of literature. The economic gains of online literature cannot be achieved without commercialization, and many online writers tend to focus on potential earnings first and foremost. Click-through rate becomes the top metric for online literature. It has become increasingly common that online writers haphazardly insert words into an established template that caters to the demands of fans and publishers.

And online literature has suffered severely from piracy. According to statistics, online literature endures annual losses of over 10 billion yuan (US$1.45 billion) due to piracy. Some writers complained that a newly released chapter is often available on pirating website within minutes. “Many writers cannot make a living because their income is all lost to piracy,” noted Yang Chen, editor-in-chief of the online literature site Chuangshi.qq.com.

Every emerging sector needs time to grow. Compared to classical literature that has existed for thousands of years and contemporary and modern literature that has been around in its current form for at least 100 years, the mechanisms of the online literature industry are not mature. However, some experts believe that online literature is rising because its output remains massive, its sustainability is encouraging and there is still huge space for its growth. With the changes of time and developments of technology, online literature itself will see constant change. According to its trajectory, online literature will be the mainstream of contemporary Chinese literature within 10 years.

“In spite of various problems, China’s online literature is marching towards maturity,” remarked Zhou Zhixiong, a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Chinese Language and Literature of Peking University and director of the Institute of Online Literature of Shandong Normal University. “Readers are always making choices and writers who survive this selection process are of the highest quality. The emergence of works that can rival Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings will just take time.”