Bollywood Brotherhood

Huo Jianqi wanted to shoot an elephant, but not just any plain elephant. The 58-year-old award-winning Chinese film director insisted that it had to be tumbling out of a boat into a torrential river while being shot.

“We were really cautious,” said Li Yue, India unit production manager for Huo’s team who had accompanied them to India to film scenes for Xuan Zang, a biopic of the seventh-century monk Xuan Zang, whose travels across India for 17 years in search of knowledge and sacred Buddhist texts made him a legend. “We did not want to harm any animal during the filming. Nor did we want our crew to come across any harm, because we knew if the elephant lost its temper, we would be in real trouble.”

After several days’ effort, the handler finally managed to coax the gentle giant onto a specially made platform resembling a boat. Then it was time for some cheating.

“We shot another frame in which the elephant was made to kneel in shallow water. To this we added other frames showing the boat capsizing to make it seem like the elephant was falling out of the boat,” Li added. “It was one of the most difficult scenes.” But all that hard work paid off handsomely when Xuan Zang fetched Huo the award for best director at the First BRICS Film Festival in New Delhi earlier this September, a curtain-raiser for the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Summit that will be held in Goa in October. It was a difficult story to produce, but what facilitated Huo's work was the Sino-Indian collaboration that led to the pooling of resources of two leading production companies in India and China. It made shooting easier in the Indian states of Bihar, where many Buddhist historical sites are located, and Maharashtra, home to India's famed Bollywood film industry. The collaboration also helped bring the cumbersome elephant all the way from Gujarat, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state, to Mumbai.

The idea of the film festival was put forward by Modi himself at last year’s BRICS Summit in Ufa, Russia. Bollywood, the Indian equivalent of Hollywood in the United States, produces 1,500 films on average every year and provides jobs to over 6 million people directly. It has been an eloquent cultural envoy for India for decades, winning hearts overseas even during difficult political and economic times.

“Look at Raj Kapoor and his film Mera Naam Joker (My Name Is Clown),” said B.B.L. Madhukar, Secretary General of the BRICS Chamber of Commerce and Industry, referring to the iconic Indian actor-director whose family has been in the film industry for four generations. “The 1970 film about a circus clown struck a chord in what was then the Soviet Union due to its universal themes of loneliness, love and courage. It also had a mix of Russian elements, featuring a Russian circus and a Russian actress, whom the hero falls in love with in the story. Raj Kapoor became a legend in the Soviet Union, and the film’s songs became immensely popular, hummed by older generations of Russians even today. It created friendship between countries and peoples.”

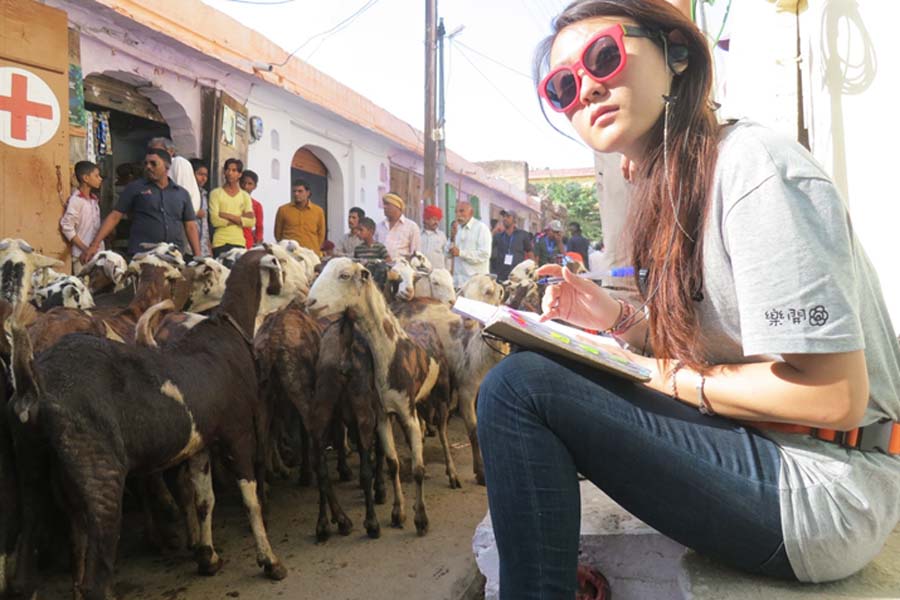

Li Yue gets ready for action for Chinese actor Wang Baoqiang’s directorial debut, Danao Tianzhu, which was partly shot in the Indian state of Rajasthan, on April 7. (FILE)

From Bollywood to China

Jonathan Tang, an engineering student in Beijing, is worried. His father, a civil servant, will retire in two years, and Tang fears it will take him much longer to establish his own career to become the family’s breadwinner. This is why he wholly empathizes with 3 Idiots, the 2009 Bollywood film exposing the hollowness of a rote-bound, insensitive education system that pushes students toward self-destruction. Told with humor and chutzpah, the film made a splash outside India as well due to the similarities reflected in other countries’ education systems.

“I love that film,” he said. “I have watched it both with my family and friends. I wish I can triumph over the system like the hero.”

Aamir Khan, who played the protagonist, and director Rajkumar Hirani then teamed up for a second film in 2014, PK, the story of an alien landing in India and making lighthearted fun of Indian foibles. PK became a box-office hit in both India and China—so much that even the Western media began commenting on Bollywood’s growing presence in China.

Los Angeles-based Rob Cains, a partner in co-production company Pacific Bridge Pictures, blogs about China’s film industry and Bollywood. He has also been writing about the China-Bollywood chemistry in Forbes. Last year, he called PK “the most successful Indian film in Chinese history” and wondered if Khan could be China’s next big star.

“Bollywood films are certainly among the most prominent and recognized aspects of Indian culture around the world,” Cains told Beijing Review. When asked why Bollywood films’ reception in China had become newsworthy for the West, he attributed it to the vast Chinese market: “China's box-office growth is of great interest to the Hollywood community. In addition to the performance of Hollywood films there, Western producers and studio executives are interested in how other foreign films perform with Chinese audiences… I have been involved in the Chinese film industry for more than 20 years, and I’ve had strong connections in Bollywood for about 12 years, so I'm naturally interested in the intersection of the two national cinemas.”

Both countries’ markets are bound to overlap even further in the foreseeable future. While Bollywood films owe their mass appeal to their picturesque and well-choreographed song-and-dance sequences, Indian audiences admire Chinese martial arts, popularized by films such as Enter the Dragon (1973), which has attained cult status. Not many are aware that Chinese action directors, especially those from Hong Kong, are highly sought after and wooed by Hollywood as well as Bollywood. Veteran action director Ching Siu-tung, popularly known as Tony Ching, won international recognition after he directed stunts in Hollywood hits like Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers(2004). In 2006, Ching made it big in Bollywood too with the superhero film Krrish (2006), for which he received two Indian awards. “He was the action director for a sequel as well, Krrish III (2013),” Li said. Nearly a dozen Chinese stunt men worked in Mumbai in the summer of 2011. “And it’s not only Bollywood films. Chinese action directors are working in regional Indian films as well.” Shankar Shanmugam, a popular director from south India, had Huang Jianming direct the action in his revenge thriller I (2015), while the martial arts scenes were choreographed by Yuen Woo-ping, the Chinese maestro whose earlier films helped launch Chinese superstar Jackie Chan’s career. Parts of the film were shot in China’s Hunan Province as well as India and Thailand. “Chinese action is very popular in India, and we are very good at it, just as India is good at singing and dancing,” said Li.

Now Chinese directors are returning the compliment, as evidenced by a new trend of Bollywood song’n’dance sequences appearing in Chinese films. In 2014, Chinese director Zhang Jianya went to Rajasthan, the west Indian state famed for its spectacular desert landscapes, fauna and colorful local clothes, to shoot The Amazing Trip to India (2014). He chose Indian choreographer Longinus Fernandez, who had won acclaim by choreographing for the multiple Oscar-winning Hollywood film Slumdog Millionaire (2008).

Although The Amazing Trip to India was ultimately canned, two other upcoming films are expected to add more power to China-Bollywood collaboration. Kung-Fu Yoga (2016) is Hong Kong director Stanley Tong's comic drama about a Chinese and an Indian on the hunt for Tang Dynasty treasure. The upcoming movie casts Jackie Chan and Aamir Khan, whose chemistry together is expected to create another bilateral hit as well as promote both countries as tourist destinations. Actor Wang Baoqiang, whose hit movie Lost in Thailand (2012) incited hordes of Chinese to go holidaying in Thailand, will be releasing the movie he directed, Danao Tianzhu on December 24 this year as Lost in India, which is expected to boost Chinese tourism in India.

Aamir Khan (center) takes a group photo with both Indian and Chinese guests at a press conference promoting his film PK in Beijing on May 12, 2015. (IC)

Tangible outcomes

According to reports, Lost in Thailand caused a 50-percent year-on-year jump in the number of Chinese visitors in Thailand when it was released. India, on the other hand, has failed to cash in on Chinese tourism despite being China’s next-door neighbor. In 2014, over 100 million Chinese went on trips abroad, and nearly 90 percent of them headed for other Asian countries. Nonetheless, India’s share was a meager 174,000 Chinese tourists. China, on the other hand, is drawing more and more visitors from India—in 2014, they numbered around 675,000.

Collaboration between Bollywood and the Chinese film industry could be a game changer. It could also create greater synergy among all BRICS film industries. “The BRICS Film Festival would be a platform for bringing industry experts from the five countries together,” Madhukar said. “This year, they discussed how there could be collaboration to make films with universal themes or on globally recognized icons.”

Russian filmmaker Galina Evtushenko and her daughter Anna, for example, made a documentary which brought to light the correspondence between Russian literary powerhouse Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi. The film, Leo Tolstoy and Mahatma Gandhi: a Double Portrait in the Interior of the Age (2016), was shown at the BRICS Film Festival, leading to discussions on the possibility of films about other leading figures such as Mother Teresa, according to Madhukar. Collaboration would bring many benefits to BRICS filmmakers. “In countries like South Africa the directors said they get no financial help from their government,” Madhukar said. “But in India, some state governments provide funding assistance. The Indian Council for Cultural Relations has a fund as well. A subject of common interest would find easier funding and a bigger market. Cross-border collaboration would also help filmmakers find new exotic locations, which in turn would help tourism. Bollywood thriller Dhoom II(2006) was shot in South Africa, triggering Indian tourists’ interest in the beautiful country.” Perhaps the best gain from the initiative is the feeling of international support generated. Aditya Pratap Srivastava is a 20-year-old aspiring filmmaker who lives in Delhi. His friends are multicultural. They include Russian directors the Evtushenkos, South African director Mandla Dube and Brazilian filmmaker Vicente Ferraz Goncalvez. “Cinema crosses all barriers and creates cultural bridges,” Srivastava explained. “All of us met at the discussions during the BRICS Film Festival to talk about the opportunities and challenges for a BRICS film market. The consensus was that co-production is the way forward.”

To learn more about how other directors work, Srivastava is getting ready to attend the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa in November. From this year, the IFFI will include a section of BRICS films. “Next year, I will go to Chengdu in China, which will host the Second BRICS Film Festival,” Srivastava added.

His thoughts are echoed by Li. “People want to be part of something bigger than themselves,” she said. “If we have good collaboration, we can bring out the best in each country.” She has been to India more than 15 times, and regardless of negative press surrounding the country, she has had positive experiences all the way: “All the people I met, all my co-workers in India, were very hospitable. Nobody ever treated me as a rival from China. And when Indian co-productions come to China, they are treated the same way. We share the same language—cinema.”

This article is reposted from Beijing Review, NO. 39 SEPTEMBER 29, 2016