China-India Ties: Trust Deficit Fuels Trade Imbalance

Since China launched the “Land and Maritime Silk Roads” initiatives in the second half of 2013, the country has spared no efforts to win a positive response from India. However, despite the fact that India is eager for investments from China, especially in the infrastructure field, the South Asian country has not been able to abandon its stereotypical view that China is a threatening rival.

India remains wary about China’s presence in South Asia. Due to its ambivalence towards China, India has never publicly voiced support for the “Land and Maritime Silk Roads” initiatives that China has proposed; but at the same time, India agreed to become a founding member of the China-initiated Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Considering that issues such as the border dispute, the Tibet issue and China-Pakistan relations will continue to cast clouds on China-India relations in the future, it is expected that steps to build political mutual trust between China and India will lag behind moves to boost economic cooperation.

In May 2015, just eight months after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to India, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, paid a return visit to China. This indicates that Modi attaches great importance to the India-China relationship. Of course, the Modi administration cannot completely avoid the problems that have long hampered bilateral relations between China and India. In the event that these problems remain impossible to be resolved in the short term, the current Indian government would like to pay more attention to reducing the trade imbalance and attracting more Chinese investments, which have become crucial for building a more intimate, progressive partnership.

‘Make in India’and Chinese investments

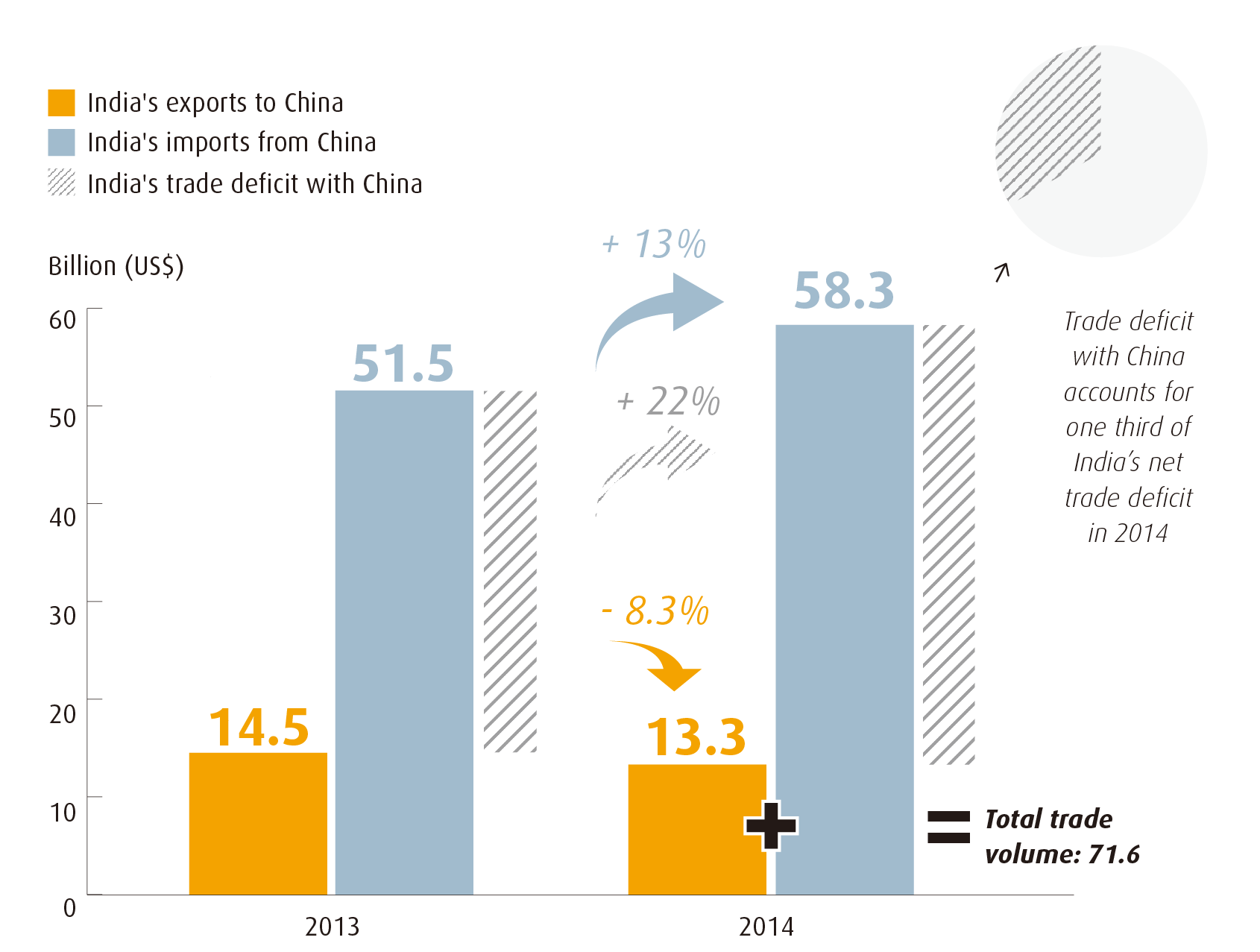

In 2014, the trade volume between China and India reached US$ 71.6 billion. Compared to the previous year, India’s exports to China dropped 8.3 percent to US$ 13.3 billion, while its imports from China rose 13 percent to US$ 58.3 billion. India’s trade deficit with China was US$ 45 billion last year, increasing by 22 percent over the previous year and accounting for one-third of India’s net trade deficit.

India’s significant trade deficit with China casts a shadow on the relations between the two countries. Because the Indian Rupee doesn’t serve as a popular vehicle currency in international trade when compared with the United States Dollar, the mounting trade deficit will pose a threat to the balance of payments (BOP) crisis faced by India. Therefore, India is keen on lowering its trade deficit. China, for its part, is urging India to further open up to China. This brings a good opportunity for the two countries to deepen their economic and trade cooperation.

A key factor behind the trade imbalance between the two countries is India’s less developed manufacturing sector. This is reflected in the structure of China-India commodity trade: The commodities that India imports from China are wide in variety and have high added value, while exports to China from India are mostly raw materials or intermediate products.

However, some Indian scholars argue that India’s trade deficit with China does not reflect its real capacity in foreign trade. They believe that it is China’s non-tariff barriers that are hampering India’s pharmaceutical, software and agricultural products, which all sell well in the international market, but have found it difficult to enter the Chinese market. According to the joint statement signed during Modi’s visit to China, the two sides agreed to “take necessary measures to remove impediments to bilateral trade and investment, facilitate greater market access to each other’s economies, and support local governments of the two countries to strengthen trade and investment exchanges with a view to optimally exploiting the present and potential complementarities in identified sectors in the Five-Year Trade and Economic Development Plan signed in September 2014, including Indian pharmaceuticals, Indian IT services, tourism, textiles and agro-products”.

Finding common ground

To achieve this goal, it will not only take a long time, but also require joint efforts at various levels. In terms of economy, the Modi administration has emphasized developing infrastructure and improving India’s manufacturing. In the first year after he took office, Modi has visited many countries to seek overseas investments to support India’s development. The “Land and Maritime Silk Roads” initiatives that China has launched aim to realize the interconnectivity of Asia and promote economic integration of the Asian region, using Chinese capital and technology. It is easy for China and India to find common ground in this process.

September 20, 1989: Representatives of China’s Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade and India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry sign the first meeting minutes of the China-India Joint Group on Economic, Trade, Science and Technology Cooperation in New Delhi, India. [by Tan Renxia/Xinhua]

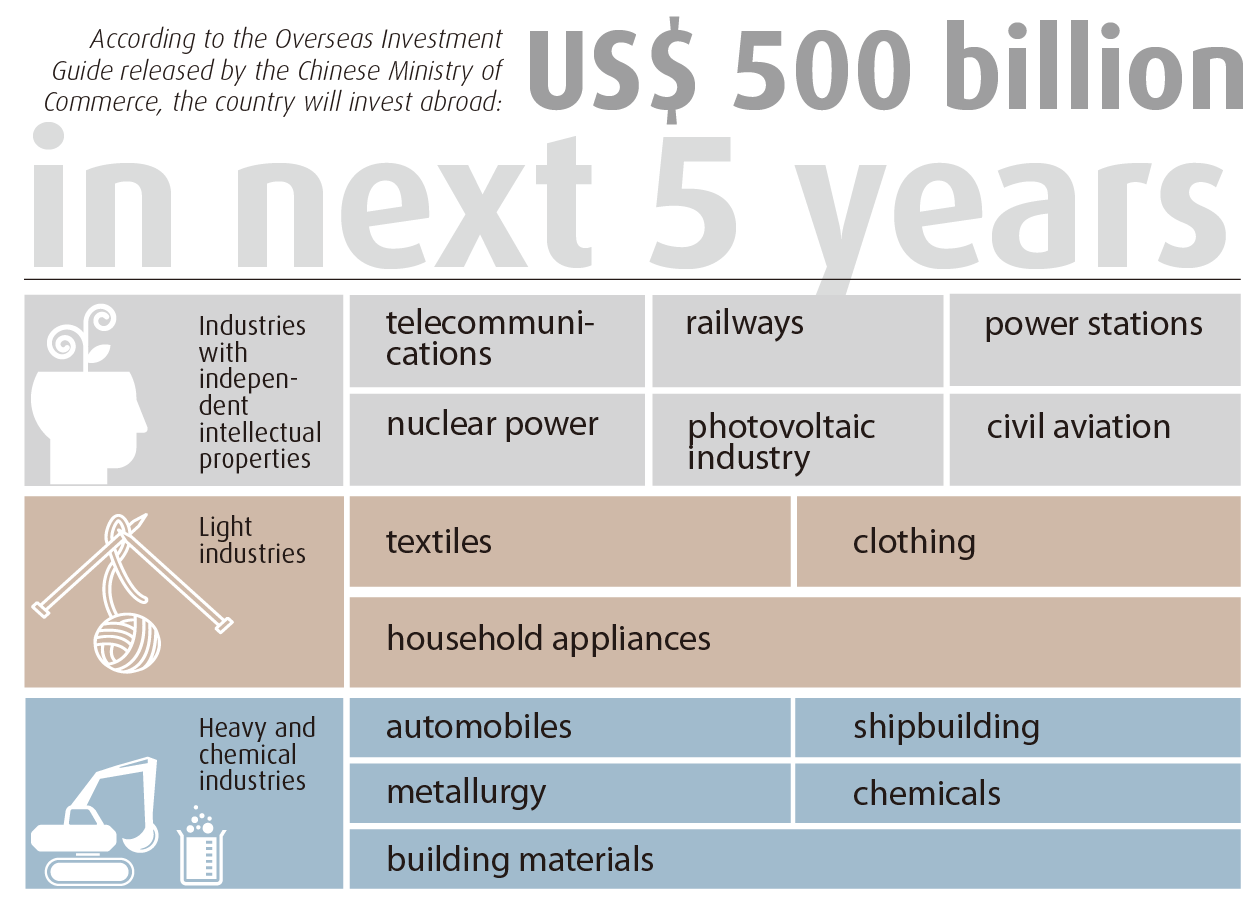

This is, after all, the basis for all cooperative agreements signed between the two countries during the mutual visits of President Xi to India last year and Prime Minister Modi to China in May. To promote the “Land and Maritime Silk Roads” initiatives, China will invest more than US$ 500 billion abroad in the next five years.

India, as a developing country with a population of 1.2 billion and a manufacturing sector accounting for less than 17 percent of the national economy, is the first choice destination for China to transfer its industries. The return of India’s economy to a track of fast growth was a “good card” that Prime Minister Modi held when he visited China. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that India’s economic growth rate will surpass China’s in 2016.

However, Chinese enterprises are yet to pay enough attention to India. China last year, in the joint statement following President Xi’s visit to India, agreed to build two industrial parks in India’s Maharashtra and Gujarat, and pledged to invest US$ 20 billion in India’s manufacturing and infrastructure sectors in the next five years. But statistics concerning foreign investment in India, released in February 2015, showed that investments from China had not yet seen an evident increase. Chinese investments in India totaled US$ 887 million, accounting for only 0.8 percent of total foreign investment in India. One reason is that Chinese investors have neither sufficient knowledge nor confidence about the Indian market. Moreover, India needs to adopt an economic policy that features greater openness and freedom, which remains a huge challenge faced by the Modi administration.

New energy, new cooperation

Prime Minister Modi plans to achieve the goal of empowering every Indian household to “have at least a lamp lit” in his five-year tenure. Considering that India has 300 million people suffering from power shortage with a net power deficiency accounting for 13 percent of total installed capacity, such a goal appears to be mission impossible. In addition, facing international pressure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions amid worsening air quality, the development of clean energy has become an indispensible solution for India, rather than merely an alternative option.

China has agreed to cooperate with India to develop nuclear power projects. It is expected that the two countries will make progress in this realm. China’s photovoltaic products have occupied half of the international market, including 60 percent of the Indian market. However, Chinese photovoltaic manufacturers are facing the dual problem of frequent anti-dumping investigations in the international market, as well as surging production costs in China.

June 11, 2015: The China-India Economic and Tourism Cooperation Forum is held in Kunming, capital of Yunnan Province. [by Chen Haining/Xinhua]

India has set up economic zones specializing in non-traditional energy. The Indian government should provide preferential policies for Chinese photovoltaic enterprises that intend to settle in such special economic zones, and eliminate discrimination targeting at Chinese firms. Meanwhile, the Chinese government could consider providing support through establishing overseas economic and trade cooperative zones. The two countries should consider setting up high-level new energy industrial parks. On account of intense market competition, the quality of Chinese photovoltaic products varies greatly. Chinese photovoltaic manufacturers, for their part, should improve the quality of their products so as to burnish their brand image in the Indian market.

Loosening visa restrictions

Due to their different industrial structures, it is impossible for China and India to solve their trade imbalance in the short term. The trade between both countries in services has just started, which will have a great potential in the future. India can reduce its trade deficit through developing trade in services with China.

Both countries have a long history and diversified culture, so tourism cooperation between them has a bright future. Currently, China and India see less than 500,000 mutual visits per year. Such a figure is unimaginable for the two most populous countries in the world. There are not enough flights between China and India, with only several major cities linked directly by air.

As a start, the two countries have begun personnel exchanges in fields such as education, medical care, finance, law, industrial design and information technology. For instance, they have initiated mutual educational certification and authentication. India’s Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) is very competitive in the international market, but its clients are mainly American and European enterprises. It should be on the agenda of the Modi administration to court Chinese enterprises, and facilitate their understanding and utilization of India’s advantage in BPO services.

However, it still remains inconvenient for Chinese to apply for a visa to travel to India. In order to promote trade in services between China and India, the two countries should loosen restrictions on visa applications so as to facilitate personnel exchanges. This is an important factor in resolving the trade imbalance. The more Chinese tourists visit India, the more tourism revenues India will earn. Moreover, with the increase of personnel exchanges, Chinese consumers will find more Indian commodities that they may be interested in, providing a stimulus for India’s exports to China. Apart from looser visa policies, the two countries should also enhance the construction of air and land transportation. Closer personnel exchanges will help to expand bilateral trade.

As two rising big powers, China and India are often likened to a “dragon and elephant dancing together”. As the English writer Charles Dickens wrote, “Don’t squeeze! The world is so big that it can accommodate both you and me.” Despite the fact that both countries still have territorial disputes and may face greater competition for energy resources and trade, it is certain that China and India will only gain more room for development by enhancing mutual trust and cooperation.

The writer, Liu Xiaoxue, is Associate Research Fellow at the National Institute of International Strategy, under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Published in the ISSUE 1 of CHINA-INDIA DIALOGUE