For India’s Chinese community, New Year is a time to get back to their roots

On the night of January 27, Mumbai resident Karyn Chung and her family will dress up in their finest festive clothes and make their way to the lone Chinese temple in the city – the Kwan Kung shrine in the Mazgaon neighbourhood. There they’ll meet several other Chinese people, who have similarly gathered from across the city. At a pre-decided “auspicious time”, the group will pray and afterward, exchange red hongbao packets, hoping for good luck in the months to come. They will be bringing in the New Year, with rituals that are similar—in spirit, if not the details— to the ones unfolding thousands of miles away in China. For India’s Chinese expatriate community of about 5-7000, scattered across their respective cities, the Spring Festival is one of the few times that brings the community together.

“My grandparents were born in a place named Meizhou in southern China,” says 27-year-old Chung, who owns a chain of hair-salons across Mumbai. The elder Chungs were the first generation from the family to move to India in search of better job opportunities. They set up home in Kolkata (then named Calcutta) which, along with Mumbai, was where most Chinese immigrants lived. The two port-cities had neighbourhoods –often referred to as Chinatowns—that were packed with Chinese hairdressers, dentists, beauticians, dock workers, shoemakers and even some restaurateurs.

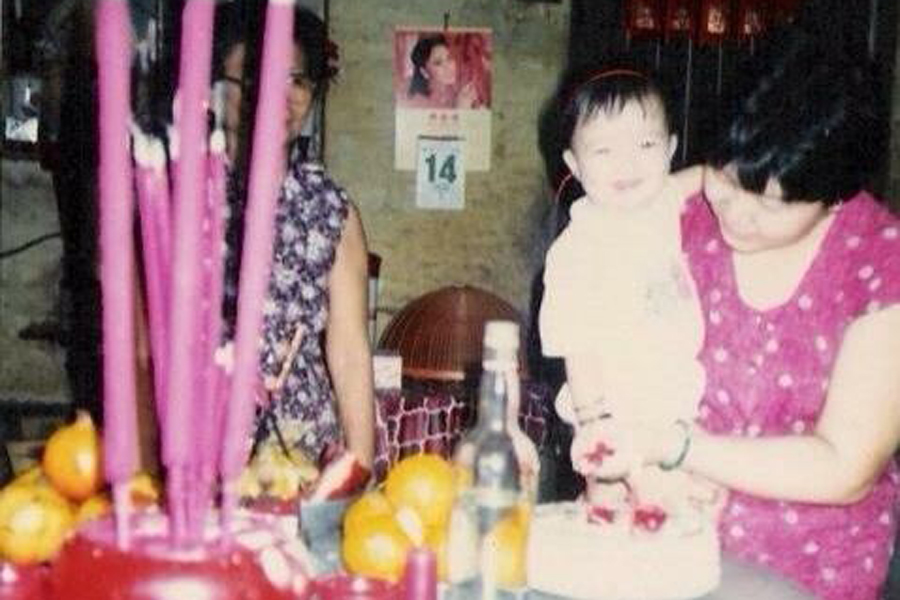

When Chung was a baby, her parents decided to move to Mumbai. There, the Chinese community is smaller and the celebrations more subdued as compared to Kolkata but mean no less to the residents.

“It’s our way of staying in touch with our traditions and culture,” says Lawrence Chang, father to two teenagers. Chang is a second-generation Chinese immigrant living in Kolkata, and married an Indian. “When the kids were young, we went on a trip to China during Spring Festival once so the other relatives there could meet them,” he recalls. “It’s hard to do that now because they have college and I and my wife have busy schedules at work. So it’s important to me that we celebrate New Year here at home.”

Because Chang’s family straddles two cultures, New Year’s Eve festivities take place on both December 31 and January 27. The former is when the teens go out with their friends and party, says Chang, but the latter is strictly time for family.

Ernest, the elder of the two, is certainly not complaining. “The food is great and I eat non-stop. That’s my favourite part of Chinese New Year,” he laughs, adding that he often gets into a competition with his sister Jessica about who can eat the most dumplings (jiaozi).

“Jiaozi are a must!” adds Cathy He, who teaches Chinese at the Inchin Closer Institute in Mumbai. Usually, for Spring Festival, He visits her family back home in Shanghai. They go out to see the fireworks, watch the Chinese New Year gala on television and settle down to a staggering table. “There are special dishes made of fish, pork, vegetables, and desserts,” says He. This year, as she is in Mumbai during the New Year holidays, He plans to meet some Chinese friends for dinner and go on a short trip later, somewhere around India.

The scale of New Year celebrations is more muted in Mumbai, adds Chung, because its Chinese community is gradually getting much smaller. Kolkata is where the celebrations are grander, with groups of youngsters playing music and performing the dragon-dance all night. They then visit different houses to collect hongbao, divide the money amongst themselves and then organize a party. Tangra, where Kolkata’s Chinatown is located, is the hub of celebration. An integral part of the Indian-Chinese community’s culture, Tangra is also where special snacks are made and sold, by groups of old Chinese ladies from their homes. Several of these, such as the prawn-potato wafers Chung loves, make their way to Mumbai too during Spring Festival. Last year, Chung had visited Kolkata with her family. “That was when I experienced the feel of New Year for the first time,” she says.

Whether they live in Mumbai or Kolkata or anywhere else in India, says Chang, the important thing is that the Chinese community gets in touch with their “old home” during New Year. He mentions how when his parents were alive, they would tell him and his sister stories of their life back in Hubei province. After they moved to Kolkata, they missed the Spring Festival celebrations in China and sought to recreate them by wearing traditional Chinese silk costumes and burning firecrackers. The entire neighbourhood would participate with great enthusiasm. “They learnt Hindi, ate Indian food but also ensured they taught their kids about Chinese culture,” says Chang. “We live in India now and this is our new home, but we shouldn’t forget where our roots are, where we came from.”

The author is editor and journalist of China-India Dialogue.