India-China Tourism: Civilizational Ties in a Modern Avatar

Journey to the West is the name of a popular Chinese classic, an imaginative rendering of the travels of the Buddhist monk and scholar Xuan Zang. In the 7th century A.D., he journeyed from China across Central Asia to India, and spent 14 years travelling in India before returning to his country with a vast collection of Buddhist manuscripts. But Xuan Zang’s epic journey was itself in continuation of a long tradition. For a thousand years before him, pilgrims, traders, scholars and adventurers had trodden the many trade routes between India and China collectively known today as the Silk Road. A pilgrimage to India — ‘the Western Paradise’ — was the ultimate dream for many Chinese. Indian sculptors, painters, artists, musicians, astronomers, mathematicians and scholars were to be found in every city along the Silk Road, and had an honored place in Xi’an, the then capital of Imperial China. Even more remarkably, these two civilizations coexisted peacefully for nearly three millennia without any significant period or event of armed conflict. Such a record between neighboring countries must be unprecedented in world history.

How is all this relevant today? The word ‘tourist’ was unknown in the days of those Silk Road travelers. But in today’s terminology (as adopted by the World Tourism Organisation), the travels of those merchants, yogis, pilgrims, scholars, craftsmen and others who frequented these routes would fit the current definition of tourism. They more than fulfilled those requirements of ‘travelling with a purpose’ and venturing well beyond their local areas; and they certainly journeyed more than overnight — in fact, for months if not years. Perhaps the first really large-scale ‘tourism’ in recorded history was between India and China.

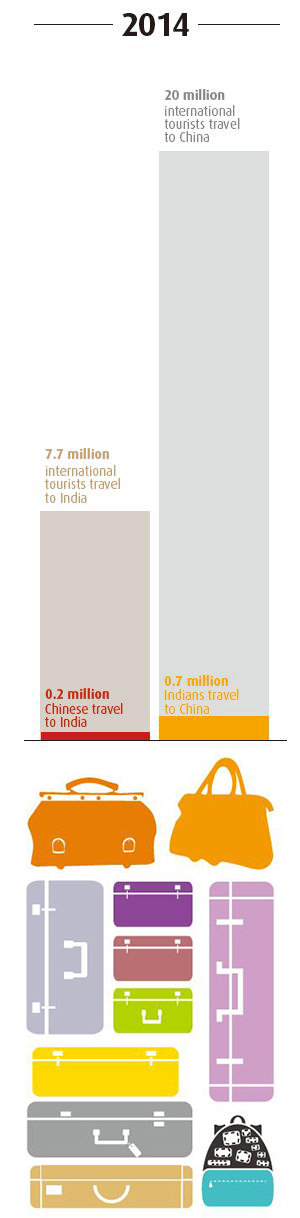

Against this glorious historical canvas, where is India-China tourism today? The story is pathetic. In 2014, of India’s 7.7 million international tourist arrivals, only 200,000 were from China—less than three percent. And, of China’s 20 million overseas visitors in that year, about 700,000 (just over three percent) were Indians (including non-resident Indians). This three percent level of mutual Sino-Indian visits looks even more marginal when set in the context of the burgeoning growth of the outbound travel business in both countries. Today, China generates a healthy outbound volume of 84 million tourists (excluding travelers heading to China’s Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan), whilst the figure for India is 18 million (estimated for 2015).

The World Travel and Tourism Council has forecast that the Asia-Pacific region would remain the growth engine for world tourism for the next 10 years. By 2020, the outbound numbers for China and India may touch 100 million and 50 million, respectively. In this broader scenario, however, India-China bilateral travel continues to languish, at levels certainly not befitting two giant, fast-growing, neighboring Asian economies. So the scope for tourism between India and China is vast. Whilst these two countries are neighbors, they need not be strangers to each other.

This combination of large outbound volumes together with rising purchasing power constitutes a powerful engine for tourism generation, and so it is not surprising that many countries are competing for a piece of this lucrative pie. Australia, Switzerland, the UK, Austria, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Mauritius, Maldives and Sri Lanka are actively pursuing Indian tourists. So are the countries of Scandinavia and East Europe, the Middle East, and even individual provinces of nations such as Italy and France. Imaginative approaches are in plenty. Britain, Switzerland and New Zealand are targeting Bollywood to shoot films in their countries. Strong advertising and attractive packages lure Indian travelers to Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand. The countries of the Indo-Chinese Peninsula, along with Thailand have also created the Greater Mekong tourism packages aimed at the Chinese and East Asian markets. South Korea, and more recently, Mongolia and Russia, have actively targeted Chinese travelers.

With this background, it is imperative that for their mutual benefit, India and China should immediately engage each other intensively to increase tourism between the two countries. Even if each country targeted only an additional two percent of the other’s outbound market, it would mean two million additional tourists entering India and one million coming into China. For India, this implies a foreign exchange inflow of over US$2 billion and at least 100,000 additional livelihoods (For every jumbo jet landing daily with 400 tourists, US$150 million is generated over the year, assuming a modest expenditure of US$1,000 per head for a week’s stay).

Important as it is, the raison d’etre for Sino-Indian tourism is not merely economic. The demonstration effect of active and peaceful human connection and cooperation between China and India will send a powerful signal to those who believe in the ‘clash of civilizations’ or in the inevitability of geopolitical ‘realism’ leading to tense if not adversarial relations between the two Asian powers. But, for tapping this multi-dimensional tourism goldmine, we must act decisively.

First of all, we must increase the awareness of India in China. At present, India figures quite marginally in the Chinese psyche. Yes, India does occupy a special place as the land of the Buddha, but this is mostly amongst the older generation. Indian films have made a visible mark; there is scarcely a taxi driver from Xi’an to Xinjiang who cannot hum the words of “Awaara Hoon”. The 1962 conflict does not seem to bother people in general and survives only as a residual political issue. There is recognition and respect for India as an IT power, and for its relatively strong English-language base. All this has not yet translated into making India a holiday destination for the Chinese.

Awareness of India should be supported through strong and imaginative measures. It is no longer sufficient just to open the quintessential government of India tourism office in Beijing. Rather, we should create a 21st Century “House of India in China” in Beijing and other key Chinese cities through a cooperative venture involving the Ministry of Tourism, representative organizations of India’s tourism industry, aviation and travel companies interested in China, the Indian Council of Cultural Relations, CII, FICCI, ASSOCHAM and NASSCOM. There should be a year-long calendar of events and programs projecting different aspects of India. Leading film personalities from China should be called upon to tour our provinces and tell their stories on television and on the internet — Jackie Chan and Gong Li could be our best ambassadors in China! Print, electronic and social media must target personal choices and experiences, with Indian fabrics, fashion, and cuisine being in full display. There is nothing like a lively exchange of views and sharing of actual experiences to create interest and curiosity about India. The best recommendations, after all, are those of friends and colleagues who have been there, done that. In the age of Facebook and Twitter, they are all over the world.

Secondly, we should launch an ambitious youth exchange program to create a new generation dedicated to friendship and peace, and the rediscovery of each other’s civilization. Young people in both countries are not prisoners of the past, and have the outlook of global citizens. Why not set an ambitious target of at least 100 youths from each district in India visiting China every year, and a similar reciprocal number from China? These journeys need not be mere government-sponsored joy-rides. With Skype and FaceTime, it is possible to ‘twin’ schools and colleges in each country, and for students in the two countries to be connected well before undertaking any travel beyond their shores. It is quite feasible to generate field projects that could be undertaken by joint student teams from both countries, studying areas of common interest. Chinese and Indian students could thus jointly discover the ecological wonders of the Western Ghats, or the mangroves of the Coromandel Coast, just as they could explore the high plateau of China’s Tibet Autonomous Region or search for fossil deposits in the deserts of Inner Mongolia.

Thirdly, we should create travel packages for the Chinese traveler, with care and attention to language, information and cuisine. Let us try novel approaches. Why not holiday offers coupled with English-language summer schools for Chinese students? What about exchange programs where teachers can teach Indians Chinese and Chinese English? Why not open the historic trans-Himalayan land routes from Sikkim and Ladakh to China’s Tibet and Xinjiang for adventure and eco-tourism? How about shooting Indian films in China and a sequel of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon being shot in India?

Fourthly, an analysis of Buddhist tourism to India over the last 10 years shows that the share of young travelers has dropped by 25 percent. This is not a happy trend, since the overall youth tourism market in Asia is growing strongly, and ‘the youth bulge’ in Asia will persist for many years. I believe that the major reason for current Buddhist tourism packages not attracting young travelers lies in the nature of the tourist experience. Tourists are transported from site to site by air, rail and bus; they dutifully go around the historic areas, take photographs, buy mementoes, perform rituals, and move on, having ticked yet another destination as ‘done’ in their diaries! No wonder that they cannot attract young people who search for meaning and relevance from the age-old Buddhist values of scientific enquiry, social service, respect for nature and peace of mind in a world that is far more complex and uncertain than that experienced by their parents.

Perhaps the remedy lies in creating a ‘new’ Buddhist tourism which is, quite simply, a revival of the oldest form of Buddhist tourism—the pilgrimage—where travelers can live out Buddhist virtues and see the results for themselves. An example has been set here by the Indian state of Sikkim. Travelers to this state can experience rural life, partaking of the local food and trying their hand at local crafts, sports, social service and volunteering in community projects. City slickers can revive their sense of wonder and connection with the natural environment through nature walks. Accommodation is simple and inexpensive, but neat and clean, with the hospitality and warmth of local families. Meditative camps and healthcare retreats provide alternative forms of healing which allow the body to display its natural powers of growth and regeneration. In every way, all these activities display Buddhism in an alive and natural way, and not as a fossilized form or dusty museum pieces.

Finally, perhaps it is possible to think even more radically and involve our South Asian neighbors in this endeavor. Can we create a transnational ‘Grand Buddhist Tour’ starting from Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, to take in the hallowed Buddhist sites of southern and northern India and Nepal, traverse the great monasteries of Tibet, terminating in Mongolia at the magnificent Erdene Zuu monastery built on the ruins of ancient Karakorum? Can we capitalize upon the reopening of Nalanda University to re-create a great upsurge of Asian students’ interest in India, as was the case two millennia ago?

Tourism on a large scale between India and China will result in benefits for people that go well beyond the economic dimension, though that in itself would be a substantial gain. It will be a massive move for peace and stability, in a world that stands perilously close to greater conflict and violence. And a befitting revival of the Silk Road—so that the trails blazed by Xuan Zang, Fa Xian, Kumarajiva and Bodhidharma may be followed by citizens of today, recreating the spirit of these two ancient civilizations in a manner sorely needed in the modern world.

The author studied Experimental Psychology at Cambridge University, and has held senior positions in industry in India and abroad. A former president of the Oberoi Group of Hotels, he serves on several company boards and is Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi, and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, London.