Internet and E-commerce to Combat Poverty

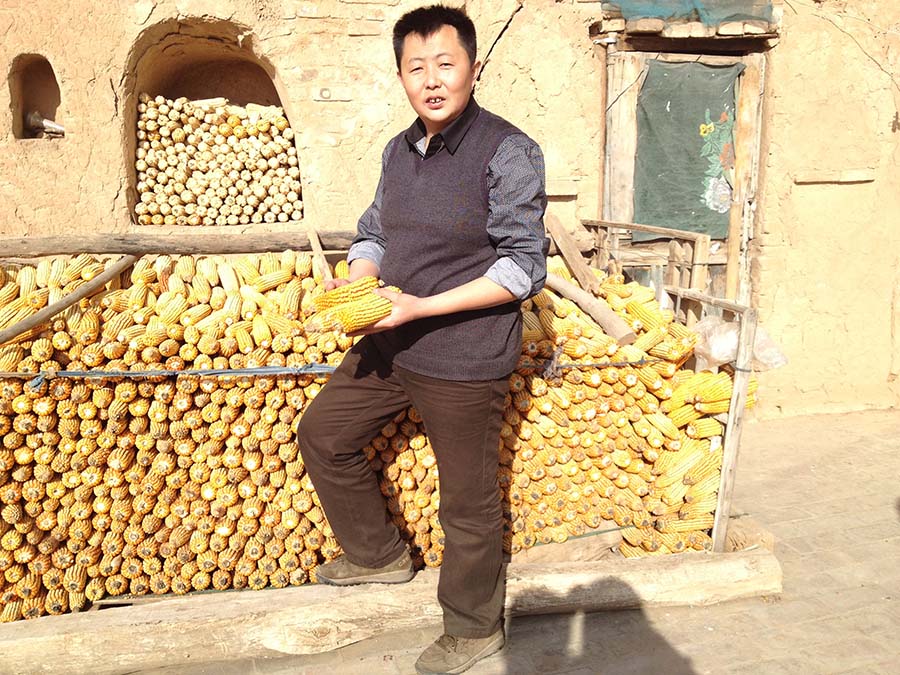

On September 19, 2014, when China’s leading e-commerce company Alibaba Group was listed on the New York Stock Exchange, Jack Ma invited eight of the company’s customers to ring the opening bell. One of them was Wang Xiaobang, who runs an online store on Alibaba’s Taobao.com (the Chinese version of eBay). Hardly one to be noticed in a crowd, Wang was born into a farmer’s family in 1978 in a mountainous village in Luliang City, northern China’s Shanxi Province. After serving as a migrant worker in Beijing for six years, he returned home with a computer and a second-hand book, Handbook for Starting an Online Store, and opened an online store selling local agricultural products on Taobao. Though hobbled by delivery delays and manpower shortage in the beginning, his store gradually overcame those difficulties and enlarged its supply base from his village to the entire province. Currently, the store offers more than 80 categories of products and receives over 200 orders daily. In 2015, its sales exceeded six million yuan.

Taobao has a huge number of customers. Although it is hard to calculate how many have shook off poverty by running online shops like Wang does, no one denies that the wave of “internet+” is sweeping across China, including its poorest villages. By 2014, there were more than 300 counties, including 21 state-class poverty-stricken counties, with Taobao shops recording sales of 100 million yuan or more. At the end of 2015, the State Council passed a decision, which incorporates “poverty alleviation through e-commerce” in the precision poverty relief campaign. In the next five years, the “internet+” strategy could benefit more impoverished people. Meanwhile, its logistics network that connects to every village will add value to underdeveloped areas.

Apart from encouraging residents in poverty-stricken regions to start businesses with the help of the internet, improving efficient utilization of high-quality educational resources and bringing good education to poverty-plagued areas by means of internet technologies is also one of the fundamental ways to end poverty. In the autumn of 2013, videotaped courses of the High School Affiliated to Renmin University of China (“RDFZ” for short), one of the country’s most prestigious middle schools, were offered to 13 rural schools in Beijing, Hebei Province, and Guangxi and Inner Mongolia autonomous region. The online education program known as “MOOC 1+1” or “Dual Teachers” was co-launched by Tang Min, executive vice chairman of the China Social Entrepreneur Foundation (“YouChange” for short), and Liu Pengzhi, president of RDFZ. To date, the new type of MOOC (massive open online courses) has enabled more than 130 schools in poverty-stricken areas to access RDFZ classes.

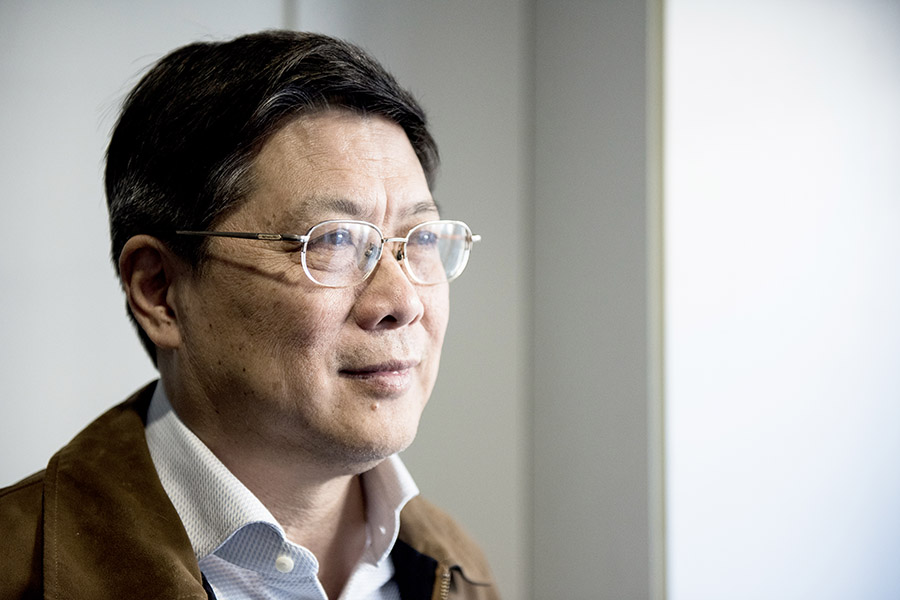

A renowned economist, Tang consecutively worked with the Asian Development Bank and the China Development Research Foundation. In 2010, he became executive vice chairman of YouChange. Tang was appointed consultant of the State Council in April 2011.

His long overseas experience facilitated him with deep insight into development inequality in different countries. He pays great attention to poverty reduction in China and other developing countries, and has realized that education is the key to poverty alleviation. From an economist’s perspective and with internet thinking, Tang launched a MOOC revolution through programs like “Dual Teachers” in the last five years while introducing the idea of MOOC into rural e-commerce training.

Recently, China-India Dialogue had an interview with Tang, whose Weibo (China’s equivalent of Twitter) account has 7.82 million followers, to discuss how the internet could be used to reduce poverty. Excerpts from the conversation are:

In today’s China, “internet+” has become the hottest word in various fields including poverty reduction. What role do you think the internet can play in poverty alleviation?

Tang: Poverty is a common challenge facing both China and India. Both countries have made remarkable achievements in poverty reduction through traditional ways. Currently, about 3 percent of China’s population still suffers extreme poverty, and traditional poverty relief effort is facing more challenges. Even if China eliminates absolute poverty by 2020, relative poverty will remain. New approaches and efforts are needed to solve the problem.

The government, along with various social organizations, has been working hard to integrate the “internet+” with poverty reduction. Most poverty-stricken areas are in mountainous regions with poor transportation conditions. If those areas can get access to the internet, locals will no longer be limited in information due to geographic remoteness. Moreover, underdeveloped education is one of the major reasons behind poverty. The internet can help poverty-stricken areas access quality online education. With the continuous development of internet technologies, there would be great potential for internet-based initiatives aimed at poverty relief.

What problems in the area of poverty eradication would be resolved through e-commerce?

Tang: E-commerce platforms can help people in poverty-stricken areas send information about their agricultural products directly to consumers, thus increasing their incomes through boosting sales. However, there are challenges to be overcome for poverty-stricken areas towards developing e-commerce: First, geographic remoteness results in higher logistics costs; second, some products have limited output; finally, local products are uneven in quality due to lack of suitable quality inspection and control standards. Moreover, online shops in poverty-stricken areas usually have low packaging capability. In view of these challenges, the promotion of e-commerce in rural areas will result in the Matthew Effect, namely, the rich getting richer and the poor becoming poorer. Generally, the comparatively rich rural areas are close to cities, thus enjoying lower transport costs. They have stronger capacity in production and product packing. So, those areas will become richer soon. Consequently, the poorer rural areas may lose in market competition, and this may make it even more difficult to sell the local products.

Therefore, poverty reduction through e-commerce is more than just promoting e-commerce in rural areas. The state needs to provide special assistance and allowances for poverty-stricken areas to develop e-commerce. For instance, the state can provide more technical training and offer subsidies to commercial logistics companies, so as to encourage them to discharge their social responsibility for poverty reduction.

Currently, YouChange is attempting an approach aimed at boosting the demand side in cities through mobilizing “consumption volunteers.” We help the first secretary of each poverty-stricken village set up a “poverty relief support team.” For example, if a public institution sends someone to act as first secretary of a rural village to help locals reduce poverty, all youngsters in the public institution will form a support team. If needed, the first secretary informs team members of products that locals intend to sell via WeChat or other means. Team members can then help marketing or themselves buy products. By encouraging consumers to buy products from these areas, more people would be mobilized to participate in poverty alleviation.

At present, China has more than 120,000 such first secretaries in poverty-stricken villages. With the assistance of volunteers from cities, they can better help locals reduce poverty.

What is the difference between this approach and poverty reduction programs on e-commerce platforms such as JD and Taobao?

Tang: Many indigenous products of poverty-stricken mountainous villages cannot be mass manufactured, and lack attractive packaging. So, they are hard to be sold on JD or Taobao. Our approach is to pay more attention to assistance via the social networking platform – WeChat, with which we help locals promote sales.

Is this approach merely an idea or has it been implemented? How did YouChange connect with poverty-stricken villages? Does YouChange cooperate with local institutions?

Tang: We have conducted small-scale experiments in some 100 villages. We plan to extend it to 10,000 villages this year. Most of those villages are located in Guizhou, Sichuan, Hebei, and Jiangxi provinces. Wherever we reach, we cooperate with local institutions, in areas such as rural supply and marketing cooperatives.

Do you think India can learn from China’s poverty reduction effort through e-commerce?

Tang: Yes, I think so. Although India lags behind China in terms of e-commerce infrastructure, it is witnessing rapid development in mobile internet. And, with mobile internet, one can access a majority of e-commerce platforms. If India wants to achieve “corner overtaking” as China did, it needs to pay more attention to the “internet+” development. Traditional poverty alleviation methods are usually time-consuming.

Why are you committed to promoting MOOC in China?

Tang: Statistics released by EDX, one of the world’s largest MOOC platforms co-founded by Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), show that the number of its students from China is only half of that from India, and the number of Chinese students who obtain diplomas from EDX is one third of that from India. Amol Bhave, a 17-year-old from India, was accepted by MIT after scoring higher than 97 percent students on EDX’s circuits and electronics course. Indian students account for 10 percent of those studying on Coursera, a free online education platform founded by two professors at Stanford University, second only to students from the United States. China should not be lagging behind in the “internet+” education revolution. In my opinion, China’s MOOC practice should blaze a new path in resolving educational inequality, unemployment of college graduates, and inadequate innovation capacity.

You said that MOOC raised hopes of solving many education deadlocks in China. How should this be interpreted?

Tang: For a long time, people believed that the key to improving education in poverty-stricken areas is solving problems concerning “hardware,” such as classrooms and teaching equipment. Nowadays, however, the major problem isn’t hardware any more, but uneven distribution of educational resources. Few quality teachers are willing to permanently stay in poverty-stricken areas. Educational quality may impact the future living standards of children. Improving educational quality in poverty-stricken areas is not only a matter of educational equality, but also a matter of ending intergenerational poverty.

The internet can solve problems that cannot be solved in traditional ways, such as bringing quality education to poverty-stricken areas. The “Dual Teachers” program has been carried out for three years and achieved remarkable effects. Today, the overwhelming majority of Chinese schools can access the internet. The prices of projectors are affordable. If the low-cost program can be spread wider, there will be an answer to ending educational inequality.

In your opinion, how can the MOOC model be extended to more areas?

Tang: Large-scale popularization of MOOC requires efforts by the government. But, public welfare organizations should carry out experiments and explorations during the preparatory period. Non-governmental and social forces are needed to promote relevant reforms. My ideal education is: first, education is more equal; second, education is more innovation-oriented, so as to cultivate talents with great creativity; finally, education benefits all, not only in-school students. With the “internet+” thinking, new hope has emerged for ending poverty, educational inequality, the digital divide, and intergenerational poverty.

Published in the ISSUE 3 of CHINA-INDIA DIALOGUE