'Make in India' Key to Solving India-China Trade Riddle

Back in 2007, Beijing had invited companies from across the world to bid for a range of activities connected to the 2008 Olympic Games. Very few Indian companies were, at the time, interested in bidding for an event that could have provided a learning – and, perhaps, life-changing – experience. I asked a senior official of India’s National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM), the industry body for Indian information technology (IT) firms, why its members were not using this opportunity. “Major Indian IT companies have their hands full with orders from the U.S.,” he said. “Profit margins are much higher in the U.S. and Europe, and it is also easy to relocate Indian professionals in those countries. On the other hand, the margins are extremely low in China.” But hundreds of U.S. and European IT, watch-making, sports equipment and infrastructure companies, who made a beeline for the Olympic opportunity, saw things differently.

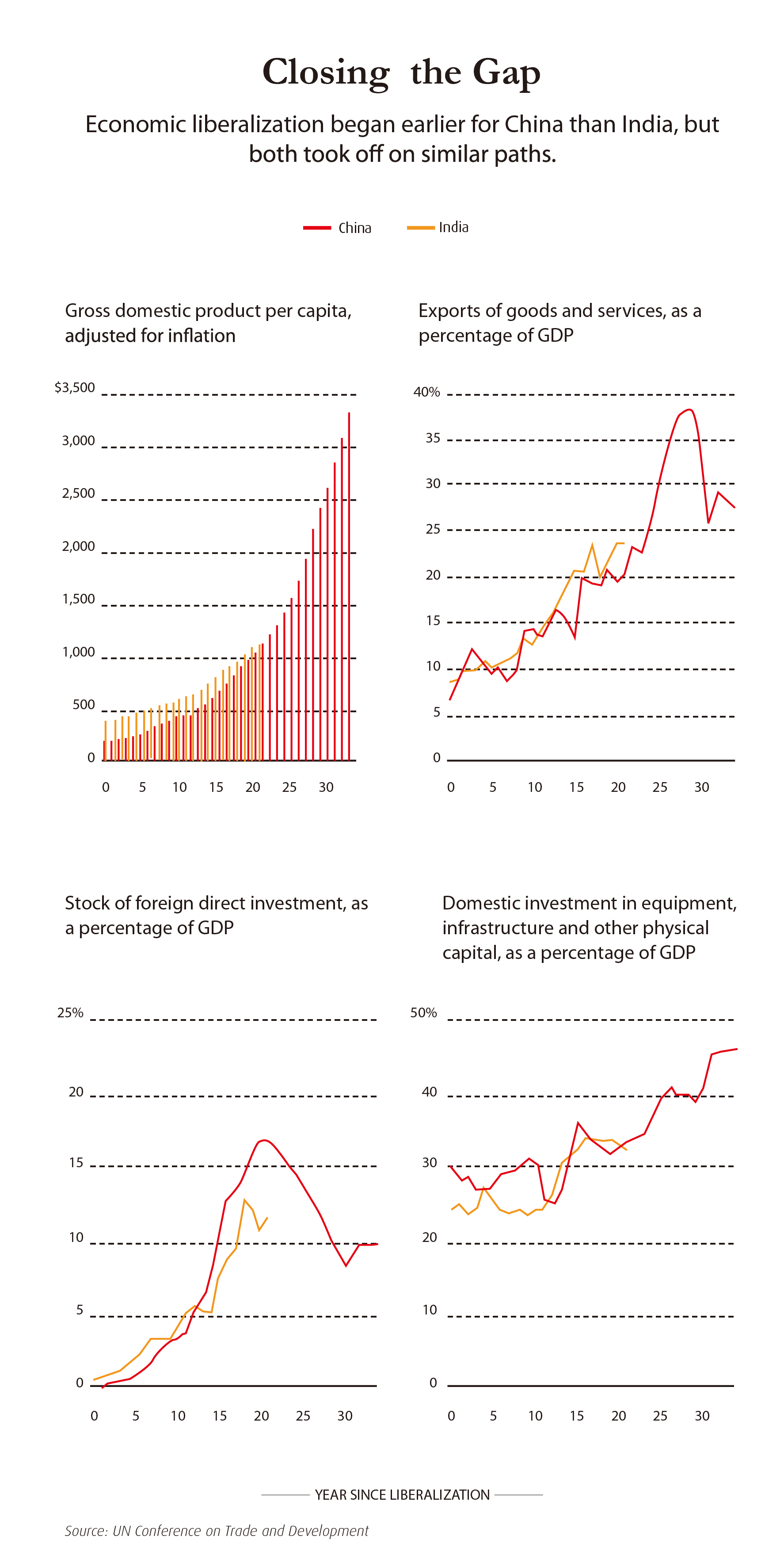

In contrast with this is the recent decision of the Indian government to buy high-speed trains and other railway capabilities from China. This was not an easy decision: the Modi government decided to bite the bullet in the hope that high-speed trains would trigger a chain reaction, fostering economic development. For a country like India, high-speed trains, in and of themselves, would not justify the high expenditure unless they act as a trigger of economic rejuvenation. No doubt a lot has changed in both India and China since 2008, especially in the manner in which the two countries have begun to see each other. Today, among businessmen on both sides of the Himalayas, there is a lot more mutual attraction. One reason is that both Indian and Chinese businesses are losing markets and opportunities in the Western world, which is undergoing an economic slowdown. China sees India and other emerging economies as markets that would partially make up for the slowdown in sales in the West. Indian companies have finally begun to consider China as a platform for learning and expansion.

This comes after years of market battles characterized by Chinese companies finding eager buyers in India, and Indian firms troubled by low demand for their goods in China. The trade gap expanded year after year. Officials in the two countries have spent countless hours writing up endless documents dealing with trade disputes and imbalances. It is another question whether finger pointing from officials has managed to find solutions to the problems. China’s biggest exports to India are telecommunications equipment, computer hardware, industrial machinery and other manufactured goods. India sends back mostly raw materials, such as cotton yarn, copper, petroleum products and iron ore. Indian companies are importing an increasing amount of China’s affordable products to meet the needs of their expanding businesses.

Trading arguments

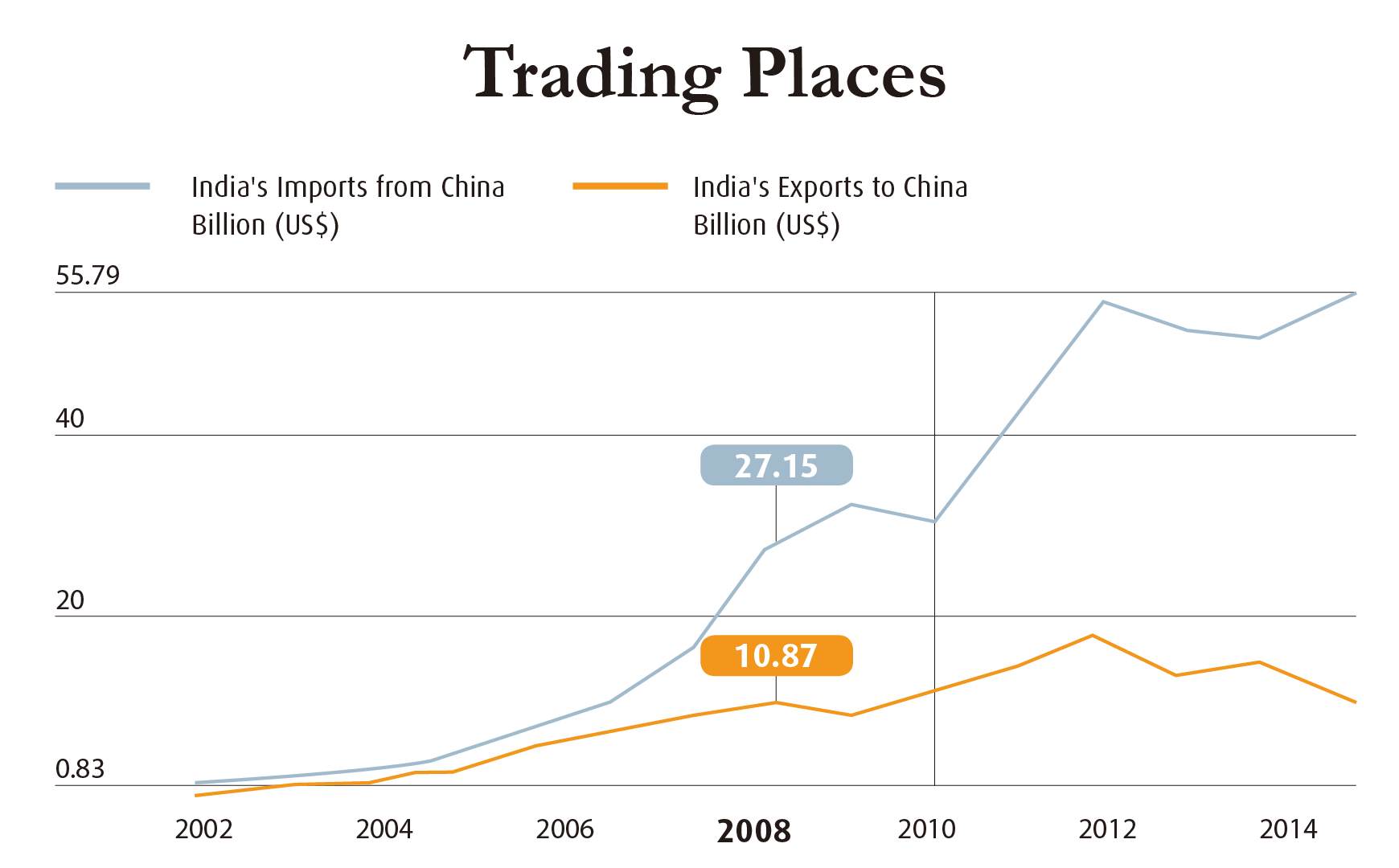

With this imbalance in trade, for more than a decade, governments of the two countries perhaps traded more arguments than goods. The overlooked irony is that each country has spent more money – and gone through steeper learning curves – in purchasing goods from distant places, rather than trade with the neighbor across the border. The simple fact is that the trade gap has continued to expand as China exported more and more goods to India, while Indian businesses struggled to gain a foothold in the China market. In 2014, India’s export volume slipped a further 8.3 percent to US$13.3 billion. Chinese exports to India in the same year climbed 13 percent to reach US$58.3 billion. The result was a trade gap of US$45 billion. China’s buying fell in 2014, causing a 22 percent increase in the trade deficit for India. China-India trade rose from US$2.92 billion in 2000 to US$71.6 billion in 2014. Seen differently, India’s sales fell from US$16.54 billion in 2011 to US$13.3 billion in 2014, instead of showing steady development. Chinese exports, on the other hand, have risen from US$52.83 billion in 2011 to US$58.3 billion last year.

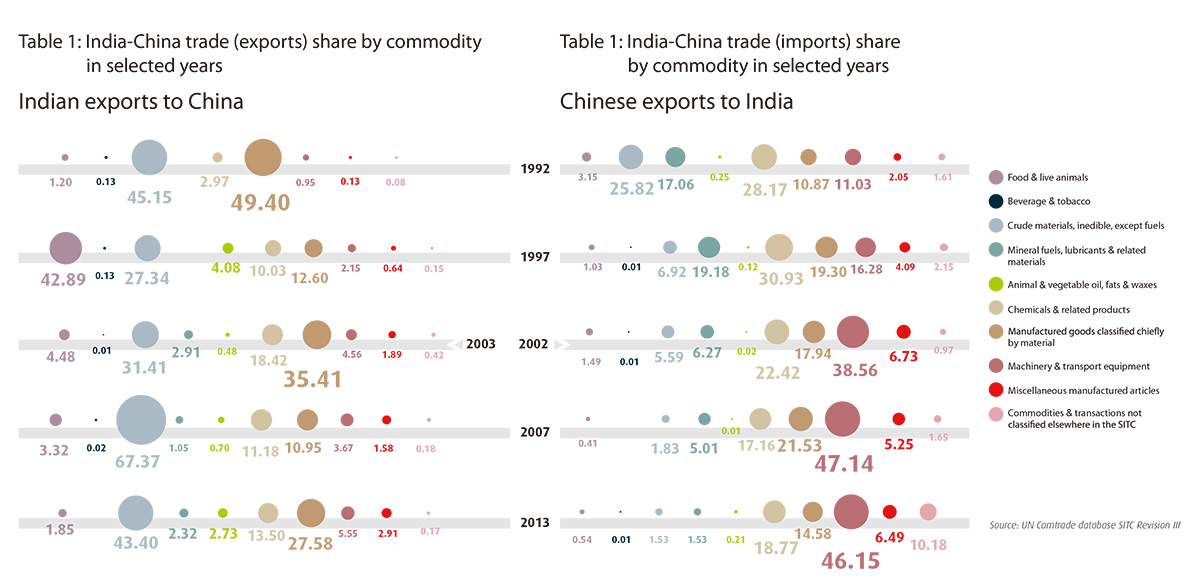

The most important item of export from India to China in 2012 was the category defined as “crude materials” which accounted for 43.3 percent of Indian exports. It was followed by manufactured goods, which contributed 27.58 percent to the export basket, and chemicals and related materials which accounted for 13.5 percent. The export category “food and live animals” contributed just 1.85 percent, although New Delhi has been asking Beijing for years to expand its food purchases, which are today dominated by imports from Southeast Asia. One stumbling block is tough quarantine requirements which exporters must meet to obtain licenses.

From China, “machinery and transport equipment” was the biggest export to India, contributing 46.15 percent. Two other major exports were chemicals and related products, accounting for 18.77 percent, and manufactured goods, contributing 14.58 percent.

Buying in China

The breakdown of trade shows not just the state of industry in both countries, but also the readiness of each country to buy from the other. The Indian craze for Chinese products is best evident at the trading hub of Yiwu in Zhejiang Province, which boasts a commodity market the size of 750 football fields, making it the world’s biggest market for small commodities. The hustle and bustle of the teeming market is fed by traders from India, Russia and Africa. Indian businessmen are an important reason for Yiwu’s survival and growth in the face of challenges thrown up by online shopping platforms. They buy goods worth over US$750 million a year – the highest by any country. Estimates of the local government suggest that 400,000 Indian businessmen visit Yiwu’s shops every year, haggling over the prices of countless goods before they are peddled in hundreds of markets across rural and urban India. Yiwu has about 250-odd Indian trading companies with permanent registration, as well as around 1,000 Indians who now reside there permanently.

For Indian planners, however, the Yiwu connection – and the overall increase in bilateral trade volume – is little consolation. After all, India is paying out precious foreign exchange to fund this imbalanced trade. Moreover, India is running the risk of hurting local industry, as businessmen find it cheaper to import from China rather than manufacture at home. Imports save Indian businessmen the trouble of investing in innovation and machinery. If the Indian government is to carry some blame for this lopsided state of affairs, it is for its inability to rein in businessmen who are finding cheaper alternatives to carrying out innovation and enhancing local production through hard work.

What is the reason for the trade gap? Peng Gang, Counselor at the Chinese Embassy in India, was quoted as saying at the Promotion Conference on China-South Asia Expo in 2013 that the imbalance was caused by various reasons “among which, a very important one is that the Chinese consumers are not very familiar with the goods from South Asian countries, and also lack of platforms for mutual cooperation between the enterprises of both sides”. “To meet the need,” he said, “the Chinese side has consecutively hosted five sessions of the South Asian Countries Trade Fair since 2007.” Other Chinese officials and experts have argued that the reasons for higher buying by India lie in the fact that India does not have sufficiently developed industrial muscle to produce things in vast quantities at low costs. “A key factor behind the trade imbalance between the two countries is India’s less developed manufacturing sector,” wrote Liu Xiaoxue, Associate Research Fellow at the National Institute of International Strategy under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in an article. “This is reflected in the structure of China-India commodity trade: The commodities that India imports from China are wide in variety and have high added value, while exports to China from India are mostly raw materials or intermediate products.”

Blocked access

Indian experts have argued that the reverse is true. China is interested in buying raw materials like iron ore to feed its steel mills and other industries, instead of procuring finished goods. Besides, the stringent government procurement system, which often includes state-owned enterprises, makes it difficult for Indian companies to sell goods to China. For instance, Indian pharmaceutical companies have said that China’s complex and time-consuming drug approval system made it difficult for them to obtain licenses to market in the country.

This is despite the fact that India is home to some of the finest drug research laboratories, which are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the United States. Pharmaceutical companies across the world make use of these facilities to obtain essential research for drug development. But pharmaceutical companies in China, which sorely lacks FDA-approved laboratories, have for years been reluctant to use these facilities, which would have made it possible for them to produce much-needed medicines at low cost. Instead, they choose the longer and more expensive route, using laboratories in the developed world.

One of China’s problems, as even government officials frankly acknowledge, is the high cost of medicines. The last couple of years have seen the government cracking down on foreign drug manufacturers, including GlaxoSmithKline, for indulging in malpractices that raised the cost of medicines. A senior official of the Chinese Foreign Ministry said in June that the government has now begun to relax rules for the import of Indian medicines into China. This comes after more than a decade of intense persuasion by India to grant market access for Indian medicines, which in turn would make it possible for China to reduce the price of medicines at home. This is a major development that could contribute to reducing the trade imbalance. It also reflects a serious effort by China to redeem a promise made by Premier Li Keqiang to make all efforts needed to reduce the trade gap and to encourage healthier development of trade relations.

Making in India

In political terms, trade relations with China were proving to be a major challenge for Indian planners around the time Prime Minister Narendra Modi landed in China in mid-May this year. Modi was already in power in New Delhi for close to one year by the time of his visit, and had come to realize that the answer to the knotty problem of the trade deficit lay not in complaining, but in producing more. Indian entrepreneurial and engineering skills, he reasoned, must be put to work by expanding manufacturing capabilities, instead of relying too heavily on the services industry. This is what explains Modi’s “Make in India” programme. He decided to engage China to make a success of this programme because this is the only country which possesses the industrial dexterity to produce machines at low costs – and even tailor-make them to the customers’ specifications.

On the other hand, China was facing a sharp exports reduction, coupled with an overall economic slowdown characterized as the “new normal” by Premier Li. This was hardly the time for Chinese leaders to tell industries to sell goods to any country for the sake of balancing a trade relationship. Neither was it easy to push unwanted buying. The answer lay in facing reality and making the most of the situation. Chinese officials came up with the idea of merging the “Made in China” strategy with the “Make in India” programme. Back in 2013, Li had proposed to India that China would like to build industrial parks, along with the necessary infrastructure, to house Chinese manufacturing companies.

Discussions between the two sides took on an earnest pace after Chinese President Xi Jinping visited India in September 2014. China has since committed to investing US$20 billion over the next five years in industrial and infrastructure development projects as part of the Indian government’s “Make in India” campaign. Chinese officials have identified 1,200 acres in Pune and Ahmedabad for the purpose of industrial parks. The Chinese plan includes establishing power equipment service centers, and manufacturing units for automobiles and consumer durables. Indian power companies who use machines imported from China have long been asking for a service center to meet industrial emergencies because rushing new equipment and maintenance staff from China, in the event of a breakdown, can be both inefficient and expensive. New service centers will also help sell Chinese power generators, according to industry sources.

Building bridges

Chinese officials say this is the start of a “win-win situation” because industrial collaboration will benefit both countries. Beijing has also proposed a Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) economic corridor project, which envisages three major linkages in terms of transport, energy and telecommunication networks. The idea is to build and encourage road, rail, air and waterways connecting the countries, besides laying power transmission lines and oil pipelines. The corridor will “harness economic complementarities, promote investment and trade, and facilitate people-to-people contacts,” an official statement said. It will pass through Mandalay in Myanmar and the Bangladeshi cities of Dhaka and Chittagong before entering West Bengal, ending in Kolkata.

China has also proposed a second, new economic corridor linking China, Nepal and India. This proposal was raised at the Xi-Modi meeting in May, and again discussed between Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Indian counterpart Sushma Swaraj in Kathmandu in June, according to Huang Xilian, Deputy Director General of the Asian Affairs Department of the Chinese Foreign Ministry. “This will be a major initiative in promoting connectivity in this region, especially between our three countries, and will help our common neighbor Nepal. We were happy that it was also positively received by Prime Minister Modi,” Huang said. “The two ministers had further discussion on this topic and reached consensus. We need to work together for the process of reconstruction of Nepal, and we need to setup a joint study group to explore the feasibility of the corridor.” China is keen to extend the Tibet rail network to Nepal, which will also help connect India on the other side. “The construction of this railway will help to materialize a dream,” Huang said. “We need to have a feasibility study on it. We need to have consultations among the three. If India shows some interest we can respond positively.”

The recent history of China-India trade relations suggests that political and border-related differences between the two countries can affect business exchanges. Business executives consider this kind of political risk as a major stumbling block. There has been a lurking fear that long-term investments might get stuck halfway owing to political differences. Companies then reason that it is best to make quick money and get out of the market – hence the focus on sales, and not long-term investment, by Chinese companies in India. Until 2014, China had signed investment contracts in India worth US$ 63.703 billion, out of which US$ 41.06 billion has been realized. India’s cumulative investment in China until 2014 has been negligible, amounting to less than half a billion dollars. These numbers are not something worth putting up on a billboard.

Political differences also act as a psychological block. People doing business in each other’s countries avoid investing their surplus funds in the host country. They tend to either bring the surplus funds back home or park them in other countries. Companies are ultimately comprised of people, and psychological considerations driven by news of border disputes can effect business decisions.

But the recent bonhomie between Prime Minister Modi and President Xi, who warmly hosted the Indian Prime Minister in his home city of Xi’an in mid-May, is a source of encouragement for industry on both sides of the border, with the expectation that it will serve as a balm to sooth the nerves of business executives who have long worried about political risks. The hope now is that these developments will boost Chinese investment in India, and start a new chapter in trade relations between the neighbors.

Relationship among the Himalayan neighbors took an interesting turn in July when India and Pakistan joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization(SCO). SCO issued a 10-year development program with participating countries which include China, Russia and Central Asian countries, pledging to coordinate their efforts on security, foreign policy and international trade. Observers said the SCO is fast emerging as a major trade bloc, which will mean easy terms of trade among its members. Heightened trade relationship between India and China is on the offing.

The writer, Saibal Dasgupta, is the China Correspondent of The Times of India. He has diverse experience as journalist and researcher working in Beijing, Hong Kong, Singapore and New Delhi for U.S., U.K. and Indian publications. He won the Jesse H. Neal Business Journalism award, the highest such award in US, along with other writers of ENR magazine, New York for 2015.

Published in the ISSUE 1 of CHINA-INDIA DIALOGUE