Monkey Keepers

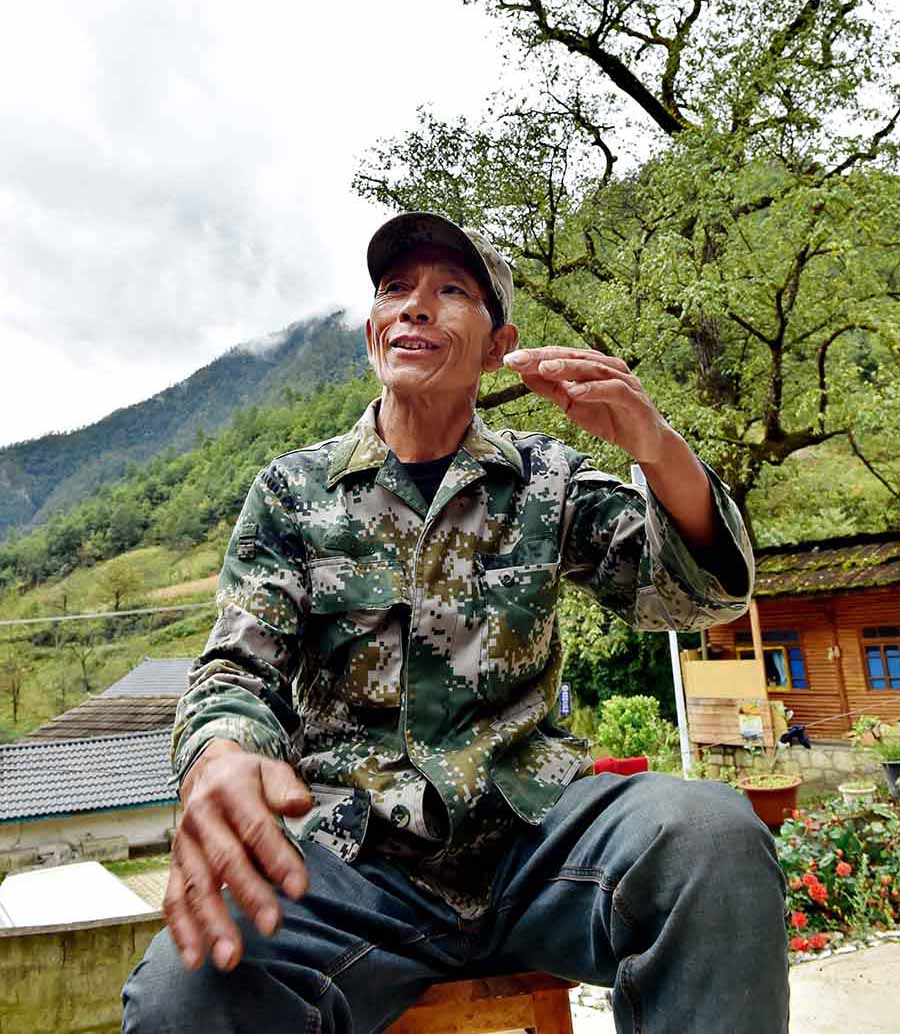

At age 64, Yu Jianhua is still a forest ranger with the Weixi Division of Baima (White Horse) Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve in Deqen Prefecture, Yunnan Province. A member of the Lisu ethnic group, Yu once subsisted on hunting and farming. Since 1998, when he joined the Weixi Division as a member of its first group of forest rangers, his focus has shifted to the protection of Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys, an endangered species under first-class state protection in China.

A French missionary first discovered the animal in Deqen during the 1880s. In Keepers 1897, French zoologist Alphonse Milne-Edwards (1835-1900) wrote the first scientific description and officially named it Rhinopithecus bieti. However, so few could be found anywhere that many assumed they were already teetering on the brink of extinction. Chinese zoologists didn’t acknowledge them until 1962 and finally began conducting scientific investigations in the late 1970s.

The White Horse Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve was first established in 1983 as the first area for Yunnan snub-nosed monkey conservation in China. Yu Jianhua was once captain of a local team of forest rangers, which has grown from four to 26 members today. Many joined the efforts to protect the forests in the nature reserve, including Yu Jianhua from Xiangguqing Village, a place where there is a forest ranger in almost every family.

In 1998, Yu Jianhua became a member of a group of forest rangers in the Weixi Division of White Horse Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve in Deqen Prefecture, Yunnan Province. Since then, protecting Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys, a rare, endangered species under first-class state protection, has become his major task. by Yu Xiangjun

Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys are primates that only inhabit alpine areas between 2,500 and 5,000 meters above sea level. Every day at 5:00 a.m., Yu Jianhua carries 10 to 15 kilograms of foods such as peanuts, pumpkin seeds and lichens up the mountain paths to feed the monkeys. Now, many of the monkeys are familiar with him, and some even take food straight from his hand.

Yu doesn’t return home until near bedtime and considers feeding those monkeys a serious business. Sometimes he has to follow the monkeys through the forests. To reach higher elevations, he must go all the way through the neighboring county. If he takes too long, it gets dark, preventing him from returning home. In that case, he spends the night in a simple cottage erected for forest rangers.

Yu still recalls one particularly snowy winter day. As usual, he prepared food for the day and set off hiking. After he left, however, the snow began falling more and more heavily, eventually blocking every path down the hills. He managed to build a fire in the cottage and spent four days trapped in the hills before he could get down.

Yu was once the captain of the forest ranger team, which has grown from four members to 26. Today, he works at the protection station under the administration of Tacheng Yunnan Snub-nosed Monkey National Park, established in 2009. “Visitors can see more than 50 monkeys there,” Yu explains. “The other 400-plus live somewhere outside the park. I go and check if they are safe twice or three times a month. Before 2004, there were only about 300 monkeys, but today the population has grown to 450 and just keeps growing.”

Yu Jianhua was once captain of a local team of forest rangers, which has grown from four to 26 members today. by Yu Xiangjun

Still, Yu is worried. “The monkeys are extremely sensitive to increases or decreases in every water resource,” he explains. Today, the entire reserve is plagued by drought and the watery regions keep shrinking, leaving fewer habitats for the monkeys. What’s worse, the beard lichen, a staple food for the monkeys, is becoming harder to collect. A few years ago, it could be found along the hills 2,800 meters above sea level, but today, it can only be found in areas with altitudes above 3,000 meters.

At 28, Yu Jianhua’s son, Yu Zhonghua, is taller and stronger than his old man. Eight years ago, he returned home after working in Lijiang to join his father’s team. Today, he leads 16 forest rangers protecting animals in regions under his administration. “In 2015, we installed infrared cameras that captured images of black bears, lesser pandas, macaques, and white-chested pheasants, creatures we only knew of from the tales of village elders,” grins the young man. The younger Yu can hardly hide his excitement when speaking of such surprises.

He is clearly proud of his father’s tremendous devotion to protecting the monkeys. “These are nomadic monkeys by nature,” he explains. “It’s impossible for them to stay in one place. They run all over the mountains. I can never find them. How does my dad do it?!”

Yu Zhonghua hopes his dad will retire, but the latter can’t be dissuaded from his trips to feed the monkeys. “My emotions are tied to the monkeys,” the elder admits. “I get upset upon seeing any of them injured, I am overjoyed to see newborns, and my heart breaks upon seeing any of them sick or dead.”

Peanuts, pumpkin seeds and lichens are favorite foods of Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys. by Yu Xiangjun

The father was clearly an inspiration to his son. “I didn’t think of being a forest ranger until I started appreciating my father’s contributions,” the younger Yu says. “Now it doesn’t feel like I have any other option.” Changes in his fellow villagers have brought him hope. “People today lead better lives thanks to the government’s targeted poverty alleviation policies,” he continues. “Every home has been fitted with a solar water heater and fuel-efficient stove, so the villagers are more willing to contribute to the campaigns for ecological protection. In the past, they cut down trees in the nature reserve to build houses and fires. Today, however, they are more aware of forest protection efforts, so they gather fallen wood instead.”

The joint efforts have resulted in solid figures. In 2013, statistics from Chinese and French biologists showed that the population of Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys in the White Horse Snow Mountain National Nature Reserve had grown from about 1,000 in 1983 to 1,800, accounting for over 60 percent of the world’s total. The younger Yu says the difference is noticeable: “In the past, it could take up to a week to find the monkeys, but today, we frequently come across bigger groups.”