Paving Memory Lane—China-India Cultural Cooperation

On September 28, 2016, a 1,600-year-old statue traveled thousands of miles to the exhibition hall of the Meridian Gate of the Palace Museum in Beijing to take part in the opening ceremony of the exhibition “Across the Silk Road: Gupta Sculpture and Their Chinese Counterparts between 400 and 700 A.D.,” which will run until January 3, 2017.

The event presents 56 sculptures dating back to the Gupta and Post-Gupta Period from the collections of nine Indian museums as well as 119 sculptures of the same period from Chinese museums in Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Shaanxi, Sichuan, and Gansu provinces and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The exhibition marks the first sculpture dialogue between the two ancient civilizations and a breakthrough in China-India cultural exchange in recent years.

China section of the exhibition “Across the Silk Road: Gupta Sculpture and Their Chinese Counterparts between 400 and 700 A.D.” by Dong Fang

Dr. B. R. Mani was born into a family of archaeologists. Before he became the director-general of India’s National Museum in July 2016, he had worked in the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) for more than 30 years. As a renowned field archaeologist, numismatist and art critic, Dr. Mani has discovered many archaeological sites in India and directed more than 14 excavation projects. He found particular sites by studying travel accounts of historical travelers, including China’s Faxian and Xuanzang.

Recently, China-India Dialogue interviewed Dr. Mani when he attended an international symposium related to the exhibition. He pointed out that Chinese sculptures adopted a new Chinese characteristic after Buddhism came to China from India. He hopes to organize future joint exhibitions between India and China of an even greater scale.

China-India Dialogue(CD): Before taking office at the National Museum, did you have a chance to work with China?

Mani: Back in 2006, before I was at the National Museum, I worked for the ASI as its additional director-general. We held an exhibition called “Treasures of Ancient India” in four cities in China. In return, we hosted an exhibition in India called “Treasures of Ancient China.” We also toured four cities in India, including the National Museum. It was also the first time we borrowed two Xi’an terracotta warriors. It was their first trip out of China. In 2011, we organized an exhibition in Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad and Kolkata. Earlier than that, I had visited China to take part in the Silk Road Conference in Xi’an. In June of this year, I visited for a conference on the Maritime Silk Road in Quanzhou.

CD: What inspired the cooperation between India’s National Museum and the Palace Museum?

Mani: The National Museum of India was co-organizer of this exhibition. We sent over 50 sculptures to the Palace Museum and some were traveling for the first time.

In fact, the Palace Museum team selected more than 80 items. However, we determined that many objects were either AA category, which cannot be transported, or so fragile that the curators did not allow them to travel.

So we had to prune down the list. Still, the screening and evaluation committee in India were hesitant about four or five sculptures and did not want us to send them, such as a terracotta head from Jammu. I insisted that these pieces go. I argued that they can raise the insurance value by letting them travel. Otherwise we couldn’t showcase the grandeur of the Gupta period. We had already cut at least 40 to 50 percent of requested exhibits. Finally they agreed, and we were able to get items from nine different museums in India, including the National Museum and some other important museums. And they approved the pieces to travel at the last minute.

CD: What measures did you take to make sure that such fragile sculptures would travel safely?

Mani: We took every precaution, especially optimal packing. The couriers are very professional. We also took some additional measures to pack the sculptures to ensure they wouldn’t get damaged during transit.

CD: How did you find the Forbidden City and the exhibition?

Mani: It is an amazing palace. In India, we also have many palaces. But most of them have lost their grandeur. For example, if you compare the Forbidden City with the contemporary palace of Mughal Period in India, the area is smaller in India, and the structures have already been damaged and lost. Sites that come to mind are the structures in Red Fort and Agra Fort, which were still standing and well-preserved before the British came. However, over the years, the sites were occupied by the British army and then the Indian army and the cells were converted into hospitals and barracks. Many of them are no longer with us today.

But fortunately, in the Forbidden City complex where China’s palaces are located, at least the structures are safely preserved. Despite the fires and accidents most have been renovated and preserved in good shape. As for the palaces in Red Fort or Agra Fort or even Lahore Fort in Pakistan, after the building was damaged, it was razed to the ground. In Red Fort, there were once at least 32 buildings, but today, only six or seven still stand. The gardens and pavilions have been gone too. We don’t have any of the Mughal grandeur anymore.

The exhibition was put together beautifully. When I joined in August, I had very little time to send the pieces to the Palace Museum, or I would have sent twice as many. I know that people in China would definitely appreciate Gupta art in the Palace Museum. I have talked with some people who were thrilled to see the structures and artistic beauty of our 50 sculptures. This is the first time something like this has been done in the Palace Museum. Maybe in the future, we will organize an even better show.

There are parallels to the Gupta period in China. Relatively few pieces are available, and it gave me the chance to see many of them for the first time. I had seen some of them in the photographs or books, but this is the first time I saw the real objects.

Buddhism came from India into China and even the art styles influenced Chinese art. Although the subject matter and some of the basic styles are Indian, the Chinese sculptures have developed a particular Chinese characteristic. Chinese sculptures have developed in their own way. The physical features, expressions and even some of the stories behind the sculptures are uniquely Chinese. It is very good interaction between India and China.

CD: How is the cooperative arrangement developing?

Mani: Now we can brainstorm future exhibitions. In June this year, I was in Quanzhou and saw the Hindu temples there. They are not there now; the remains of those temples and sculptures are in the museum. I was just discussing with some colleagues the idea of an exhibition involving these sculptures or the materials from those Hindu temple remains from Quanzhou. In India, we have the largest 14-Century blue-and-white Chinese porcelain piece, which I have written about in the catalog. We can combine such things as part of the Silk Road Exhibition. We can do this exhibition in the National Museum in Delhi and maybe in the Palace Museum and anywhere else in China.

Another good theme is silk. Direct contact between China and India was ongoing from the first or second Century B.C. to late medieval times either via the Maritime Silk Road or land roads. But new evidence suggests that interaction may have begun even earlier. Silk was the primary export from China via the Silk Road. Now we have found silk in India that dates back some 5,000 years. Although we are not quite clear if the silk was from China or there were simultaneous developments in China and India, there was definitely some connection. We have also found evidence of Jinanxiu (济南绣), a type of Chinese silk, in Sanskrit. These types of evidence must be explored further—in disciplines such as archaeology. History is essential to inspire research.

When we organized the Treasures of Ancient China in India last time, we focused on the idea of showing objects that people in India hadn’t got a chance to see, for example, pottery. As we understand, China was able to make very good pottery in the 9th Century during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and India should have had high demand for chinaware during that period of time.

CD: What of India’s experience in heritage conservation and excavation should China learn from?

Mani: China and India can learn from each other. In India, conservation is a state subject. But both the ASI and the state archaeology department have limitations. The state governments have meager funds. The ASI has a shortage of manpower, and its attention is frequently diverted to other countries like Indonesia, Myanmar, Vietnam and Cambodia, where Indian archaeologists are working. The best conservators have been sent to review. The governmental process is full of roadblocks to getting sanctions and approvals, things like that. Even when funds are actually ample, procedural delays still impede the work. In India, we still use the conservation manual that was finalized and published by director general of the ASI in 1921. International charters were not even available at that time.

Moreover, I have found that in many countries, the principles of conservation are not followed strictly. That is the case with China too. In China, the mindset is more about renovation. Renovations are also being done by some of our colleagues in India, but they’re going against the principles too. Basically, we don’t believe in renovation. We only believe in conservation. If you have a dilapidated structure, you have to keep it as it is. All you can do is ensure that it doesn’t further deteriorate and stays as close as possible to how you found it. Not only in China, but also in Iran and other countries, if there are some dilapidated structures and blueprints are available, the entire thing is renovated. Do you replace everything to restore it to new or save the evidence of what once was? There is a difference between India and China.

CD: How do you think technology will influence cooperation between India and China?

Mani: We can do much more now. This evening I was just sitting with a company that was showing how to record an area with drones as well as 3D scanning for backups. In the last three or four years, we have started performing such high tech work. If Chinese experts are interested, they can also do it in India like they have done in China’s Tibet. They beautifully documented the sites there. If they come, they can document sites like Ellora where we have large caves and cave temples. That would not only be very exciting for the public but also a permanent enhancement of the records.

CD: In an interview with Indian media, you mentioned that you have learned of sites from travel accounts of various travelers, including Chinese. Can you give us an example?

Mani: As we all know, Faxian and Xuanzang visited India. They mentioned a number of particular Buddhist sites and cities that unfortunately are little known today simply because they’re not there anymore. You follow their route and direction, you come across big sites and you can also cross-reference names in those sites, and sometimes they match with old names, but sometimes they have changed. With the correct information and archeological records at the sites, you can locate new ancient sites. A well-trained archeologist can identify the period of time or area of new findings. A good command of knowledge about culture and literature would greatly help archeologists in locating the sites.

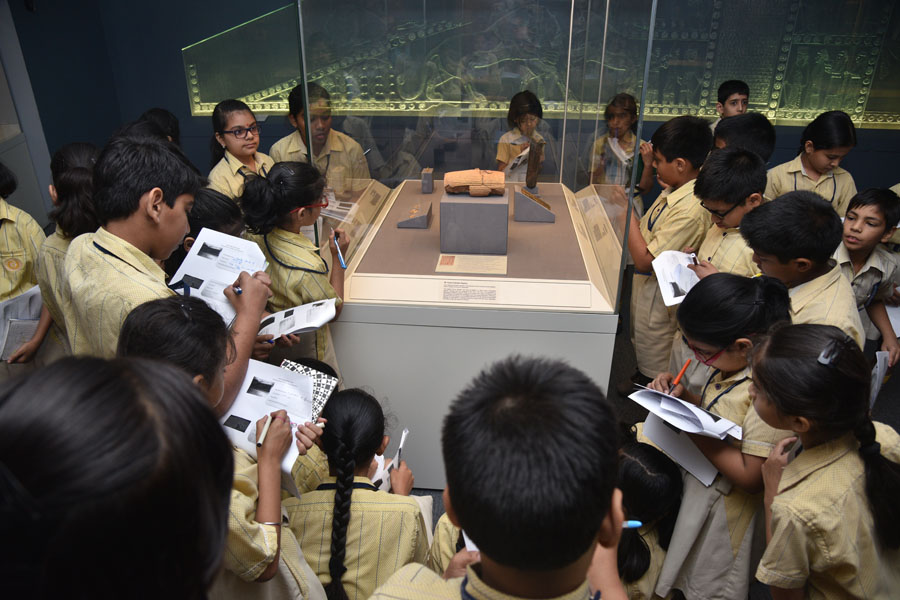

Workshop on Shahnameh: story telling and oral tradition. Courtesy of the National Museum in New Delhi.

CD: Do you feel any difference between cooperation with Chinese museums and working with Western museums?

Mani: We are more interested in cooperation with countries of Southeast Asia because of a common origin of culture. Western countries and even the West Asian countries have completely different cultures. We should first know more of our own local culture. India is already a large country, and China is even larger. If we cooperate in areas ranging from culture to economics, we can become the greatest region of the world. If we can facilitate communication and exchanges between peoples of Asia, that would be a great start.

CD: How did you find politics poses its influence on cultural cooperation between our two countries?

Mani: Of course. We have to ensure mutual understanding. Once we develop mutual understanding, we can also develop cultural exchange in other fields. But we first have to have mutual understanding in politics. At the moment, China and India have relatively good relations. If we can develop this relationship further, it would benefit both countries.