Rebranding the Past: Groundbreaking Cultural Experiment in China’s Ancient Villages

Pingshan is a small but extraordinary village in eastern China’s Anhui Province.

Historical records show that 289 years ago, during the reign of Emperor Yongzheng of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Pingshan native Shu Lian saved the emperor’s life and was awarded the title of “imperial guard” and gifted construction of a memorial temple for his efforts. At the time, most residents of the village were from the Shu clan.

Due to their innate awe and respect for the supreme rulers, for two centuries, locals carefully preserved the memorial temple and its plaque with the characters for “Imperial Guard.” Not until the 1950s did villagers with minds pointed firmly towards the future consider dismantling the memorial temple’s wooden pillars and iron components to support the nation’s “iron and steel production movement” aiming to surpass Britain and catch up with the United States. In the 1960s, furniture and relics housed in the memorial temple were smashed to pieces. When people became desperate to get rich, any surviving wooden components, doors and windows were removed and sold or used for other construction— just as the Shu clan’s presence in the village was declining.

In 2014, when film producer Zhang Zhenyan first visited the village, all that remained of the memorial temple was a dilapidated gate with the faded “Imperial Guard” plaque. Part of the 15-by-41-meter memorial temple site was absorbed into a vegetable field. Before that, it once became a commercial skating rink. Still, the exquisite sculpturing, superb carving and nearly collapsed gate in Huizhou architectural style awed Zhang.

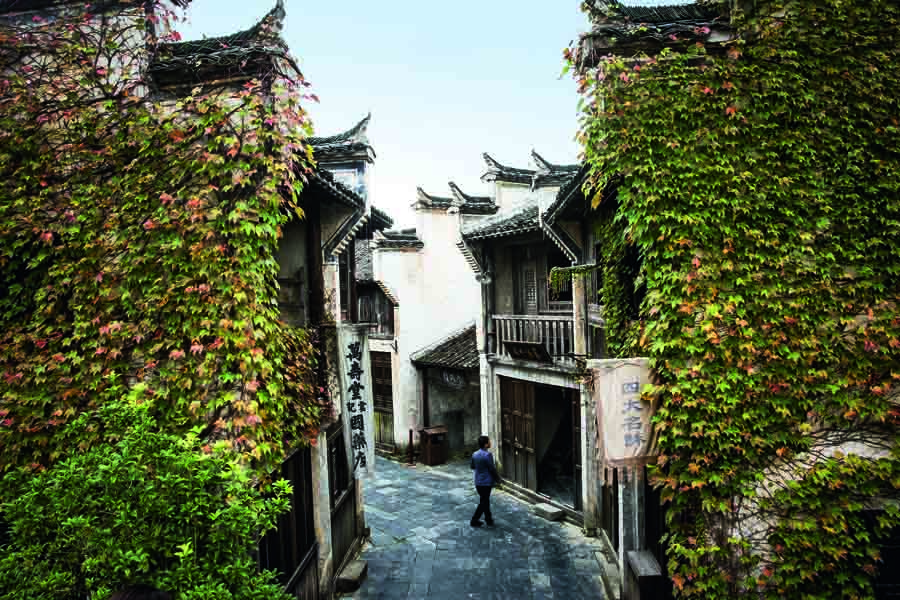

A panoramic view of Pingshan Village and its surrounding hills from the top floor of the Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel.

Born in 1952, Zhang worked as a producer for internationally-renowned director Zhang Yimou for more than 20 years. He spent his childhood in a shikumen (traditional Shanghai-specific architecture) alley, where he witnessed the grandeur of European-style villas and experienced the dignified, elegant lifestyles of yesteryear’s upper class via his grandparents. At 11, Zhang went to Beijing to live with his parents who were engaged in foreign trade there. They lived in a quadrangle residence shared by several households. In 1969, 17-year-old Zhang worked as an “educated youth” in Heilongjiang Production and Construction Corps, like many Chinese youths at that time. There, he became a trained chef. Every day, he got up at 5 a.m. to prepare breakfast for 500 colleagues. To this day, Zhang remembers the recipe and steps to cook deep-fried dough sticks by heart.

In 1976, Zhang returned to Beijing after seven years in the production and construction corps. He then joined China Youth Art Theater as a scenic designer. In the early years of China’s reform and opening up, the theater had a pioneering influence, especially by introducing foreign dramas and spreading modern Chinese drama. Zhang participated in productions including Galileo, The Merchant of Venice, and Red Dresses Are in Fashion. When Zhang was a child, the only available news media in China were People’s Daily, PLA Journal, Hongqi, China Pictorial, PLA Pictorial, and Nationality Pictorial—as well as eight revolutionary model operas. Little to read was available, nor were other forms of entertainment. In this context, that generation of Chinese people suffered anxiety due to physical and mental scarcity alike, and many developed hoarding habits. When he was young, Zhang began to learn painting and became obsessed with collecting things. He now holds a wide-ranging collection of things from every corner of the world: more than 20,000 pieces of glazed tiles from old European-style villas in Shanghai of the colonial era, nearly 100 film projectors, various antique phonograph records, contemporary and modern Chinese and foreign paintings, fireplaces, wooden boats, and even refrigerators. His collection may seem diverse, but everything is related to the Art Deco style of the late 19th Century.

When Zhang saw the nearly-collapsed gate of the memorial temple in Pingshan Village, he was struck that it would be the perfect home for his collection. He decided to convert the crumbing shrine into a boutique hotel and decorate it with artifacts he collected. With the injection of his artifacts from Shanghai, the hotel would create something new to rural tourism. Just as the treasures and artworks collected by Western explorers from around the world inspired European aristocrats to transform lifestyles during the Age of Discovery from the 15th to 16th Century, he hoped his contribution would inspire locals and visitors alike.

After a year and a half of design, artisan recruitment, construction and decoration, his Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel finally opened.

A tourist sips a cup of coffee in the lobby of the Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel. On the shelf behind him are film projectors collected by Zhang Zhenyan.

After rainfall, the hills around Pingshan Village become shrouded by mist, and the trees become especially green, creating a fairytale ambience. In the first rays of the morning sun, the black tiles and white walls of traditional residences glisten like miniatures. A group of young people gather at the front gate and in the backyard of the Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel every morning. Most are students from art schools from across the country. Art students have frequented the village to sketch since the 1950s. Despite their simplicity, local landscapes and residences invited oscillating colors and lights, making them ideal subjects for art.

Though varied in background and profession, visitors to the hotel share one thing in common: They are all fairly welloff. Rooms go for 1,500 to 2,000 yuan (US$217-290) per night. Once an active film producer, Zhang is not only an artist, but a street smart deal-maker adept at dealing with all sorts of people. The hotel and its eight rooms are a miniature world, and Zhang is the soul of the establishment with his grace, gentility and welcoming voice.

Today, Pingshan is home to 365 households, of which more than 30 earn annual incomes exceeding a million yuan. As the village becomes a popular destination, many young residents who once sought jobs in cities have returned. Mr. Wang, the village’s Party chief, was once a migrant worker. He visited the boutique hotel after it opened and opined that Zhang had enriched the village’s cultural ambience and inspired residents to recognize the value of their old dwellings. Now, everyone pays close attention to the protection of local buildings.

A native of Pingshan Village born in the 1970s, Mr. Han once served in the army and now works as a cab driver. When Director Zhang Yimou shot his film there, Han was hired to transport props. Later, he became a regular contractor for film crews needing drivers. When asked whether he felt happy living in such an ancient residence imbued with cultural profundity, he replied, “I still would prefer a new home because these are so familiar to me—it’s just like appreciating the fragrance of flowers you live with every day. Unfortunately, now local farmers are not allowed to expand their residences for the sake of protecting historical buildings. Even enlarging a window is forbidden.” Typically, the windows of traditional Huistyle residences are too small to let in ample light and fresh air.

Han operates a family hotel with six guestrooms that receives about 2,000 tourists annually. The relatively humble rooms in his hotel are priced at only 100 yuan per night. However, the rate can be doubled or even tripled during peak season. “Everyone wants to follow in the footsteps of Zhang Zhenyan’s Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel, but it’s not easy without business expertise and ideas,” he sighs.

Prior to his boutique hotel project in Pingshan, Zhang launched another project to rebuild the ancient village of Xiuli in Yixian County, Anhui Province. The restored village features 60 architectural complexes comprised of more than 100 Hui-style residences. “Hui-style architecture is characterized by circular balustrades and mortisetenon joints, usually supported by 86 pillars without a foundation,” he explains. “Consequently, such buildings are easy to dismantle and reassemble. In a week, we moved 60 old residences from an area 50 kilometers away.” Furthermore, Zhang collected a lot of components from old buildings such as beams, pillars and tiles from nearby villages to aid in the reconstruction of Xiuli Village.

A commercial street in Xiuli Village, where the film My Own Swordsman was shot.

Zhang spent five years on the project from securing construction permits to design, engineering, and decoration. Eventually, a restored Xiuli Village integrating traditional architecture and modern amenities took shape in a 9-hectare area that was once total wasteland. “Many detailed designs I intended for Xiuli Village have yet to be completed,” laments Zhang. “The project as a whole is still more like a rural family hotel than a masterpiece like the Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel.”

During the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), some aristocratic and wealthy families in northern China migrated south to Huizhou Prefecture (today’s Anhui) to escape war. Similar migrations occurred in the Western Jin (265-316), late Tang (618-907) and Northern Song (960-1127) dynasties, shifting northern China’s wealth, talents, culture, technology and lifestyles southward. Distinctive Huizhou culture is a fusion of indigenous and alien cultures.

Today, accenting the Imperial Guard Boutique Hotel are art students wandering Pingshan Village, bustling bars blaring noisy music, old women hawking vegetables and snacks on the street and taxi drivers working for film crews. Everything hearkens to Zhang’s collections: diverse and eclectic, with a sense of inclusiveness.

The author is executive editor-in-chief of China Pictorial.